Constellation Software - Deep Dive

Full investment Thesis - Constellation Software

1. Introduction

Welcome to my second deep dive of the year! I’ve had a lot of fun researching and writing about Constellation Software.

Constellation Software is interesting on so many levels: the way it was built from the ground up, its unique structure, the way employees have skin in the game, the diversification story, and let’s not forget: its performance over the last few decades. Since 2010, the share price has risen a whopping 6,500%.

There are many lessons to be learned from Constellation’s story; not just about running a business, but also about company culture, establishing principle-based guidelines, and focusing on core competencies. Mark Leonard is easily one of the most inspiring and unique CEOs of the past few decades, and what he has built will likely remain unparalleled for years to come.

I aim to cover all of that in this deep dive. Please keep in mind that I am not a financial advisor, nor am I an expert in this particular field. This is simply me sharing my research with all of you.

I hope you learn a thing or two and enjoy the read. Now, let’s dive in!

Please like and share or comment this post if you thought it was valuable. It helps me out tremendously and ensures that as many people as possible see my work.

2. Why does the opportunity exist?

2.1 The drawdown

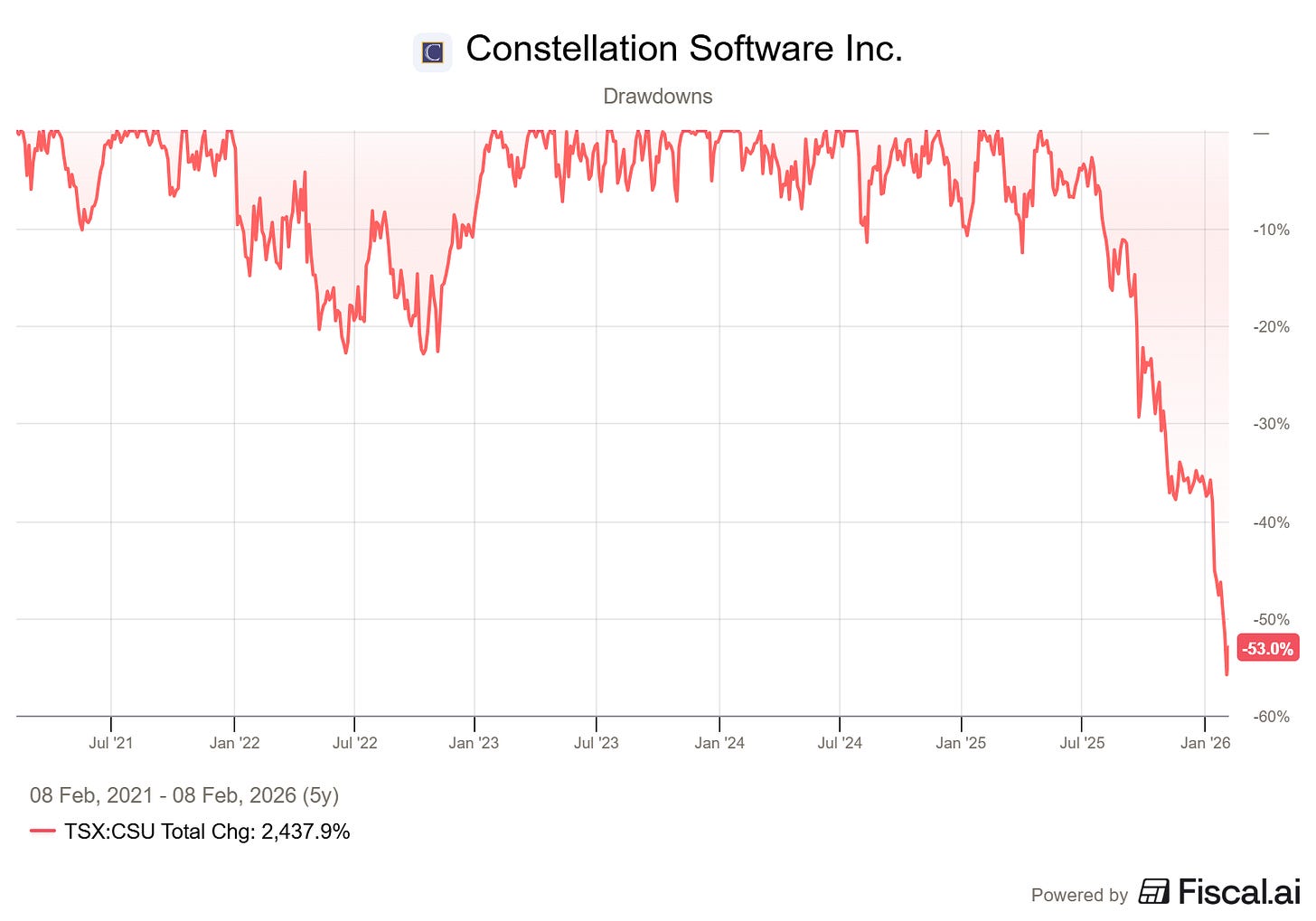

Constellation Software (CSU) is a company that I’ve been following for a while now, but I’ve never pulled the trigger. My main concern was: the ‘‘steep valuation’’. Stupid in hindsight, because such a high quality company deserves a steep valuation. But now, over the past months, something unique has happened.

As of couple months ago, CSU’s stock price is in free fall. The share price has fallen more than 50% from it’s all-time high. Unprecedented for CSU.

Before this drawdown, they had never experienced a drawdown bigger than 20%, so this is very unique and it warranted more research in my opinion.

So I was curious, why on earth is the stock falling like this? I found three major reasons:

Mark Leonard stepping down as CEO due to health reasons

Uncertainty of the impact of AI (tools) on Constellation’s businesses

Worries that the addressable TAM might be limited (the amount of companies that can be acquired in the VMS-sector)

I’m going to address address all three of them first, before we look into CSU deeper. This will already give you a good insight in what is going on, before we explore the the other parts of the company

2.2 Mark Leonard (CEO) Stepping Down

So, shares falling on this news I can completely understand, not saying it’s fair, but it’s reasonable. Mark Leonard was (and still is to this day), the visionary behind CSU’s success. He built the company from the ground, applied his values, applied his standards, and made CSU to what it is today. If the grounding father leaves a company, that hurts.

But in my opinion it does not warrant a sell-off like we’ve seen these past months. What Mark Leonard has been working on for the past decade, is making sure the company does not resolve around one single person. The business is multi-layered with different operating units and subsidiaries. There are many different smart people that run these units individually, and to this day, with great success.

After Mark Leonard stepped down in september, he was replaced by Mark Miller. With Mark Miller, they seemed to have found a worthy replacement. He has been with Constellation Software for decades and led major units like Volaris, and has deep experience executing the same decentralized, buy-and-hold approach. Note-worthy: Volaris was one of the best performing units of CSU when Mark Miller was running the show. They actually had a slightly different approach than other segments and the parent company.

Instead of sending FCF back to the parent company, Volaris reinvests it’s FCF almost immediately into new, smaller acquisitions within its own "ecosystem." Volaris uses its own FCF to fund its growth, effectively acting as an autonomous “compounder” that doesn’t need capital from the mother company.

So to sum this up: I think CSU’s business structure can really weather the storm after Mark Leonard stepped down. The whole company was built and organized to not be one-person-focused. It was not like Mark Leonard was signing of on all the acquisitions before he stepped down. And I believe with Mark Miller, they have found an excellent replacement. While no one can replace the charismatic visionary Mark Leonard himself, I think Mark Miller has the experience and knowledge to do very well. Only time will tell.

2.3 AI Impact

This is probably the big one at the moment. All software companies are being heavily sold off due to fears of AI interrupting their business models. In my opinion, these worries are generally overstated, and for CSU in particular. I’ll try to explain what I’ve come to that conclusion in the next section.

I think the big theme around AI disrupting software companies, is that the barrier-to-entry will be a lot lower due to AI advancements and vibe-coding. Software can be easily recreated and improved upon with AI. While I believe the basic premise to be true, I also believe this does not heavily impact CSU’s business model (as of now), as the barrier-to-entry to most of their businesses was already very low to begin with.

These are such niche businesses, that could easily already be disrupted, but the appetite to actually do so has been very low. And I believe it will stay that way.

The TAMs for most of the software companies and markets CSU invests in, is very very limited. They are unlikely to be attacked by bigger firms or companies that are looking to disrupt by using AI. There’s simply not that much money to be gained by doing so. Switching costs for the existing companies using the software, would be very high and let’s not forget, also very inconvenient. The software they have covers their needs (and maybe more), so why would they switch?

Keep in mind, the software is usually mission critical for these companies, and the overall costs are very low, often below 1% of total cost. The risk of losing, or worsening a key program/software for their business is not to be underestimated. Think of it this way: would you change or switch a software-package, just to reduce like 0.2%-1% of your costs, but have the chance to ruin your whole business?

Would you change something that works, that does the job, just to save a few bucks?

And in the meanwhile risk losing a relationship and service that has worked for many years?

AI is also still highly data dependend, it needs a LOT of data to be effective. Most of these so-called disrupting niche software companies lack just that, data. Outsiders simply don’t have the data to interrupt. If anything, the existing companies are way ahead, because they DO have the data needed to train these models, if they ever wish to do so.

Because there is so much discomfort in the software space now, CSU might even have the chance to acquire new businesses at reduced valuations, BECAUSE of these AI threats. PE firms are moving away, valuations are getting cheaper and that might actually open up more possibilities to CSU.

Could AI negatively impact CSU as well, yes of course. We should not close our eyes for this. But I doubt it will be in the near future. Things might progress in a different direction in the long-run, but that’s just something monitor very closely. I believe it is still very hard to predict where AI or AGI will end up in the next couple if years.

Knowing CSU, they will address this during their next AGM, and that should clarify a lot of how they currently view this AI threat. They’ve never shied away from being blunt and honest, and I expect just that in the next AGM.

Mark Miller addressed the AI concern in his latest call in October, here is what he had to say:

After checking in with his business units and customers:

-There didn't seem to be yet any concern about that (AI changing the competitive landscape - and new entrants in the market) so far. One of the things important to note, as always, with our businesses in Constellation, we tend to be fast followers.

Our business leaders, particularly our better business leaders, are usually quick to respond to changes inside of their markets due to moves their competitors make or new entrants make into the market.-

- I've not seen anything, any impact on pace or valuation. Not at all. Stay tuned if there's something else. I haven't seen anything so far-

Will AI have an impact on CSU? No doubt. But the severity of it all seems overblown to be. And the impact CSU will have on the companies they own, by simply implementing AI themselves seems underappreciated.

It’s not like they are gonna sit and wait, and roll-over and let it all happen.

2.4 Limited TAM

The last reason of the recent sell-off is investors are worried about Constellation’s TAM getting limited and their struggle to consistently redeploy FCF at a high IRR. They worry there might not be enough prospects to acquire at interesting valuations. This thought is further supported by the premise that AI might disrupt parts of CSU’s current portfolio, on top of limited the expansion possibilities. A double whammy.

While I think it is undeniable, that it is getting harder and harder for CSU to continue their growth path of the last decade, simply by the sheer volume they have to allocate to maintain their growth, there are still a tremendous amount of companies that are not on CSU’s radar or still have not been acquired. The VMS-market is not yet saturated

In the end, CSU might have to look for different and bigger acquisitions to be able to deploy all their cash. And that could prove to be harder than it seems right now. A bit more on that later in the deep dive.

I would argue negative sector sentiment might even open up more possibilities. As valuation are likely to get cheaper and competitors less interested in the overall market, CSU could step in and take advantage.

Let’s not shy away from being critical, CSU will have to execute very well to keep up with the growth they showed in the recent years, but I believe they can very much sustain their growth level in the next few years, regardless of AI disruptions.

3. Constellation Software as a company

3.1 Definition

So what does Constellation Software actually do. Here is what they say about what they do themselves:

We acquire, manage and build VMS businesses. Generally, these businesses provide mission critical software solutions that address the specific needs of our customers in particular vertical markets.

Our focus on acquiring businesses with growth potential, managing them well and then building them has allowed us to generate significant cash flow and revenue growth. Using a combination of proprietary software and market expertise, we provide software solutions designed to enable our customers to boost productivity, operate more cost effectively, increase sales and improve customer service and satisfaction.

Many of the VMS businesses that we acquire have the potential to be leaders within their particular markets. We target the VMS sector because of the attractive economics that it provides and our belief that our management teams have a deep understanding of those economics.

So, basically they are a so-called ‘‘multi-acquirer’’. They specialize in buying and managing software businesses that develop and maintain vertical market software.

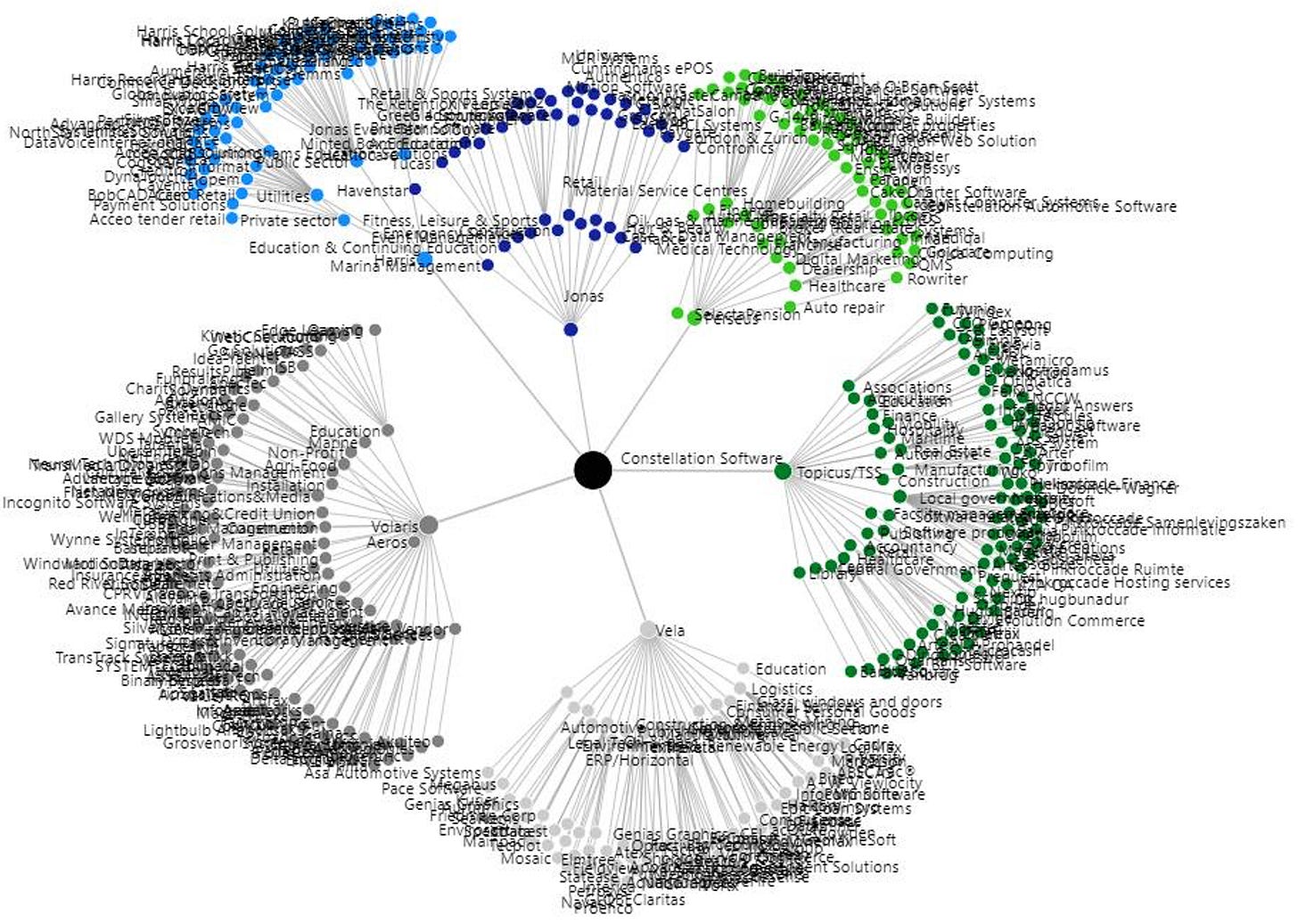

Constellation doesn’t try to micromanage the companies they buy. They are organized into six large Operating Groups), and under those groups are over 1,000 individual business units.

Local managers keep running their businesses. Constellation provides “best practices” and financial coaching but lets the founders and companies run like they used to do.

Their head office is located in Toronto, Canada and they currently have about 64000 employees.

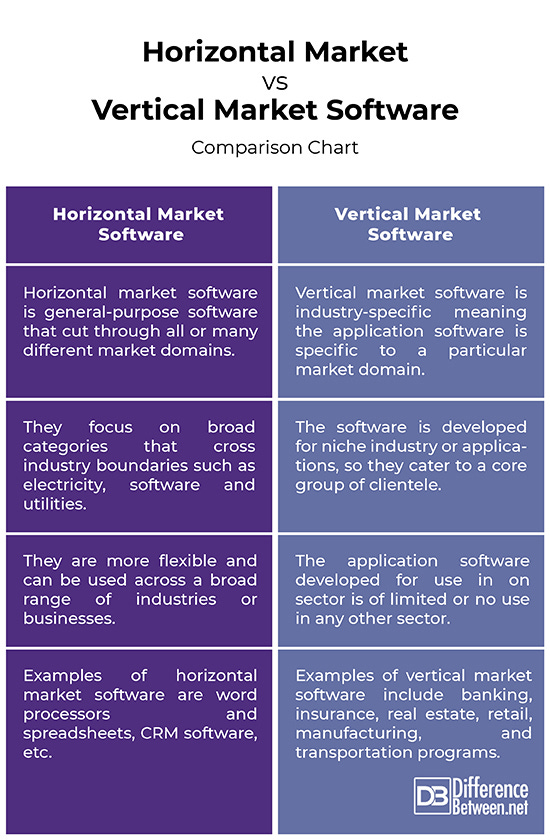

3.2 What is VMS?

VMS is software designed to meet the specific needs of a very particular, niche industry. It targets one specific industry, it usually has very limited competition, a small market size and a high level of customization.

I think a good example is bus scheduling. Think of a system that was specifically built to keep track of where all the buses are and how they should be scheduled. Which ones are due for maintenance or need refueling. There will be absolutely no other use-case for software like this, but it’s a core product for bus companies, and it really helps them to optimize their productivity and keep things running properly.

So, the software is built and used, intensively. But more importantly, it’s built specifically for this niche/sector. Since the TAM (total addressable market) is so small, there’s really no incentive to try to launch new and better software. As long as the current software suffices, there is no need to switch to other new or more fancy software. Of course, the current software needs to be updated and stay relevant enough. But that is what CSU focusses on as well, keeping the current software up-to-date and optimized for their specific use-cases.

The important thing to keep in mind here, there’s almost no upside for new entrants. The TAM is usually not big enough, expansion likely minimal, as the addressable market is usually very stable. We already talked about switching costs, which might be the highest barrier for new entrants to overcome.

HMS is the exact same opposite: that is software that is designed for a wide portfolio of different industries and sectors. Maybe the best example is Microsoft’s Office software. That’s so broad and generic (but good), that it can be used in almost every company in the world. So, general-purpose build, widely applicable and high level of flexibility. The complete opposite of VMS.

3.3 Culture

I think one of the most important aspects of this company is it’s culture and history. The visionary behind all of this, is Mark Leonard. We will go a bit more in-depth into his profile, history and vision for CSU in the next chapter.

For now I want to highlight what he has established in terms of corporate culture, his insights, his foresight, but especially his focus on values and ethics, because this permeates in every corner of the company. This is what makes CSU so unique.

Here are a few company values that really highlight the unique culture within CSU.

Large is not always better: Mark Leonard’s core belief is that large organizations inevitably become bureaucratic and slow. To combat this, he structured Constellation as a collection of over a 1000 independent businesses. Diversifieng like this requires true vision and execution. Not just on a company but also on a personal level. You have to surround yourself with like-minded and equally smart people to pull this of. And Mark Leonard managed to do just that.

CSU is a safe haven: they have famously sold only one business in their entire history (and Leonard publicly expressed regret over it). This “buy and hold forever” promise allows them to acquire companies from founders who care more about their employees’ long-term future than getting the absolute highest bid from a “slash-and-burn” acquirer. CSU is known for being amongst the weakest bidders in take-over ‘‘wars’’. That does not withhold these company owners to still chose for CSU, as they are not looking for just the best price.

Skin in the game: Executive officers are required to invest a large portion of their bonusses (75% of their after-tax bonus) into Constellation common shares (or since 2025 they can also invest in companies they acquire), which are then held in escrow for several years

Down to earth: Mark Leonard’s own personality, which is private, intellectually honest, and avoidant of publicity, has trickled down into the entire company. You notice it in their communication, which is clear and to-the-point. And importantly: non-hyped and self-critical. While one could argue their communication style is boring, I believe it to be very helpful and insightful. They are brutally honest, and don’t shy away from admitting faults and addressing headwinds or difficulties. A good example of this approach is the fact they only do 1 earnings call per year. They believe quarterly calls just provide noise, and do not attribute to their long-term value and approach.

Mark Leonard has built CSU into something that is not focused on day-to-day shenanigans and drained with what some would argue controversial rules and company culture. But the ''boring'' aspect of it, is something I actually really like. What you see is what you get. And there is a lot to like in what you get.

CSU is more focused on execution and living up to core values, rather than dealing with hype and day-to-day market sentiment. They are not trying to influence the stock price, rather the opposite. They are focused on their long-term strategies, and do this by following core principles built on years of excellent leadership and performance.

4. The Management Team

Let's talk management. Because when investing in CSU, you are basically saying: I trust management to allocate capital better then I would be able to do myself. You are not only giving trust to upper management, but you also place trust in the management layers leading the separate operating units.

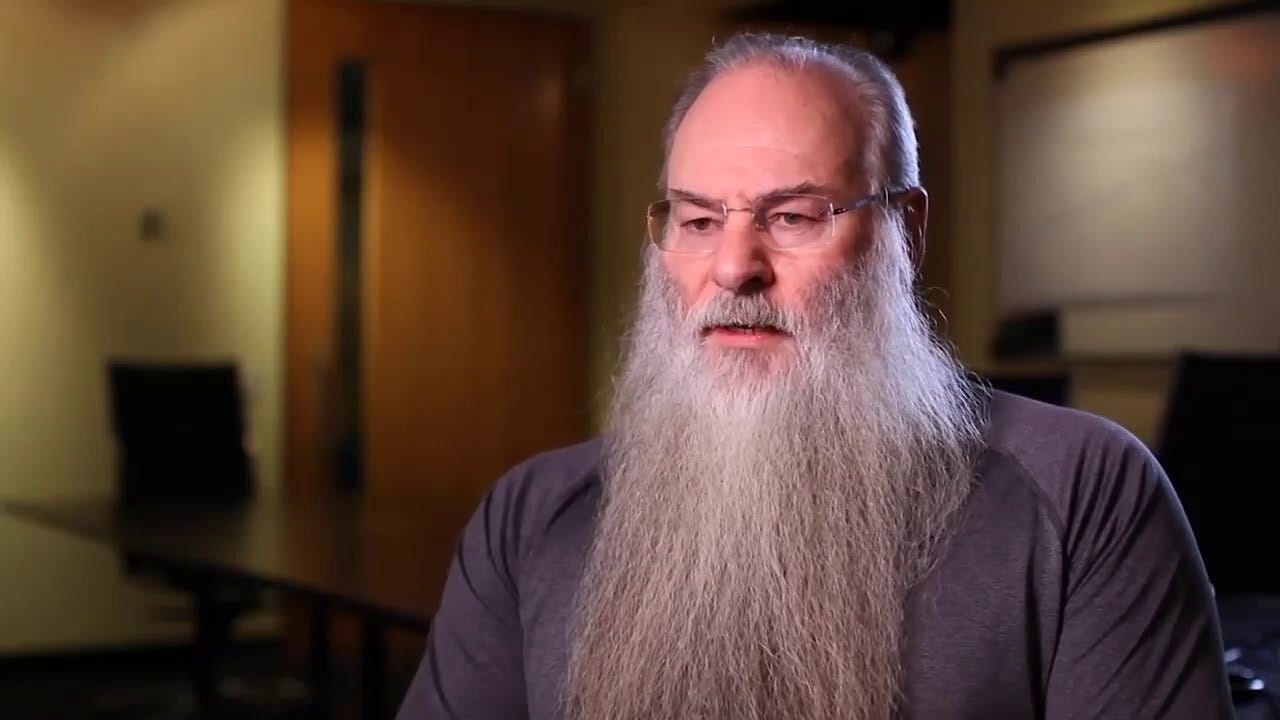

Before we start with current management, I think we have to talk a bit more about Mark Leonard himself. Because, if you think CSU, you think Mark Leonard.

4.1 Mark Leonard - Founder

Mark Leonard is the visionary behind and the founder of CSU. Mark Leonard’s journey at Constellation Software is the ultimate story of a venture capitalist who decided to stop hunting for “unicorns” and started building an unstoppable army of “workhorses.”

After spending over a decade in the VC world, he realized that small, niche software companies were actually goldmines, but they were being ignored because they weren’t flashy or easy to sell.

So, in 1995, he took $25M and a wild idea to Toronto, founding Constellation with the goal of buying these specialized businesses and, unlike almost everyone else in finance, never selling them.

For nearly thirty years, Mark operated like a “corporate monk.” He became famous for his extreme privacy, refusing to give interviews or pose for photos, which only made his legend grow as the company’s stock price began to skyrocket.

By the time he stepped back from the President role in late 2025 due to health reasons, Mark had turn CSU into a $90B company. Not a bad ROI ha. He proved that you don’t need to be the loudest person in the room to win.

He’s well-known for his annual letters in which he shared his wisdom and vision with the world, showing that patience, discipline, and a genuine love for “boring” software could create one of the greatest wealth-generating machines in history.

Let’s hope he has a speedy recovery and we might see him back in some shape or form someday!

4.2 Mark Miller - Current CEO

After Mark Leonard stepped down, Mark Miller was appointed as the new CEO. Mark Miller has worked with CSU, and in particular Volaris Group and its subsidiaries for more than 30 years.

He co-founded Trapeze Group in 1988, which was the first company acquired by CSU in 1995. Since joining Volaris Group, Trapeze Group has expanded on a global scale. The focus of his role at CSU has been on growing and developing exceptional leaders, while continuing to acquire great companies that they buy and hold forever

Mark Miller also currently serves on the boards of Lumine Group, Modaxo, ventureLAB and VoxCell BioInnovation.

He has not appeared in many public settings yet, but I think his introduction call last October says all about what he wants to do with CSU. When he was asked the question what he would do differently from Mark Leonard, this was his answer:

I really think it's business as usual. Just continue to push ahead with our existing strategy. I appreciate that sounds like an easy answer, but I think we just continue to push forward, continue to learn, and try to get better at what we're doing within the organization. There's a lot of opportunities to improve how we do capital allocation, operate our businesses. We'll just continue to focus on the same things that we always have here at Constellation in a completely decentralized fashion.

He is not looking to push his own agenda or vision onto CSU. He just wants to continue to do the things they did (because they worked) and improve on them.

He seems like a very straightforward down-to-earth guy as well, just like Mark Leonard. His focus will be on large investments and preparing the company for new leadership in the next decade.

There is not a lot of public information on the rest of the management team. So I’m going to keep it brief and to the point for the rest of them.

4.3 Bernard Anzarouth - Chief Investment Officer

Bernard Anzarouth joined CSU in 1995. He worked closely with the VMS businesses to identify and pursue opportunities for platform and tuck-in acquisitions and to establish licensing or distribution arrangements.

Before joining CSU, Anzarouth was AVP Business Development for Ascom Inc., a Swiss-based technology corporation from 1993 to 1994. Prior to that he held various positions with IBM. He holds a B.Eng. in Electrical/Computer Engineering from McGill University and an MBA from the European Institute of Business Administration (INSEAD).

4.4 Jamal Baksh - Chief Financial Officer

Jamal Baksh has been with CSU since 2003 when he joined as Controller of the Jonas Operating Group. Jamal is currently the Chief Financial Officer. Prior to this role, he served in a number of senior executive roles within Jonas and Constellation including Vice President of Finance for Constellation reporting to the Chief Financial Officer. He is a Certified Management Accountant and holds an Honours Bachelor of Mathematics degree from the University of Waterloo.

4.5 Farley Noble - Senior VP

Farley started with Constellation Software Inc in 1999 and has held CFO and senior M&A roles at head office and operating groups, including Jonas Software and the Volaris Group.

Since April 2021, he has led CSU’s head office Large VMS Investment Group. Farley also took a 2.5 year sabbatical from Constellation between 2019-2021 as the CEO/Co-Founder of a startup in the decentralized investment space. He is a CPA(CA) and holds a Bachelor of Business (Honors) degree from Wilfrid Laurier University.

4.6 Summary

So, to briefly sum this up. Constellation’s team is highly experienced. All board members have been with the company for dozens of years, and have had the chance to incorporate Mark Leonard’s vision into their own business and work ethic.

I believe these people (and many others at CSU) together can fill Mark Leonard’s big shoes. It won’t be easy, but they’ve been trained and seasoned in this business and sector for many years.

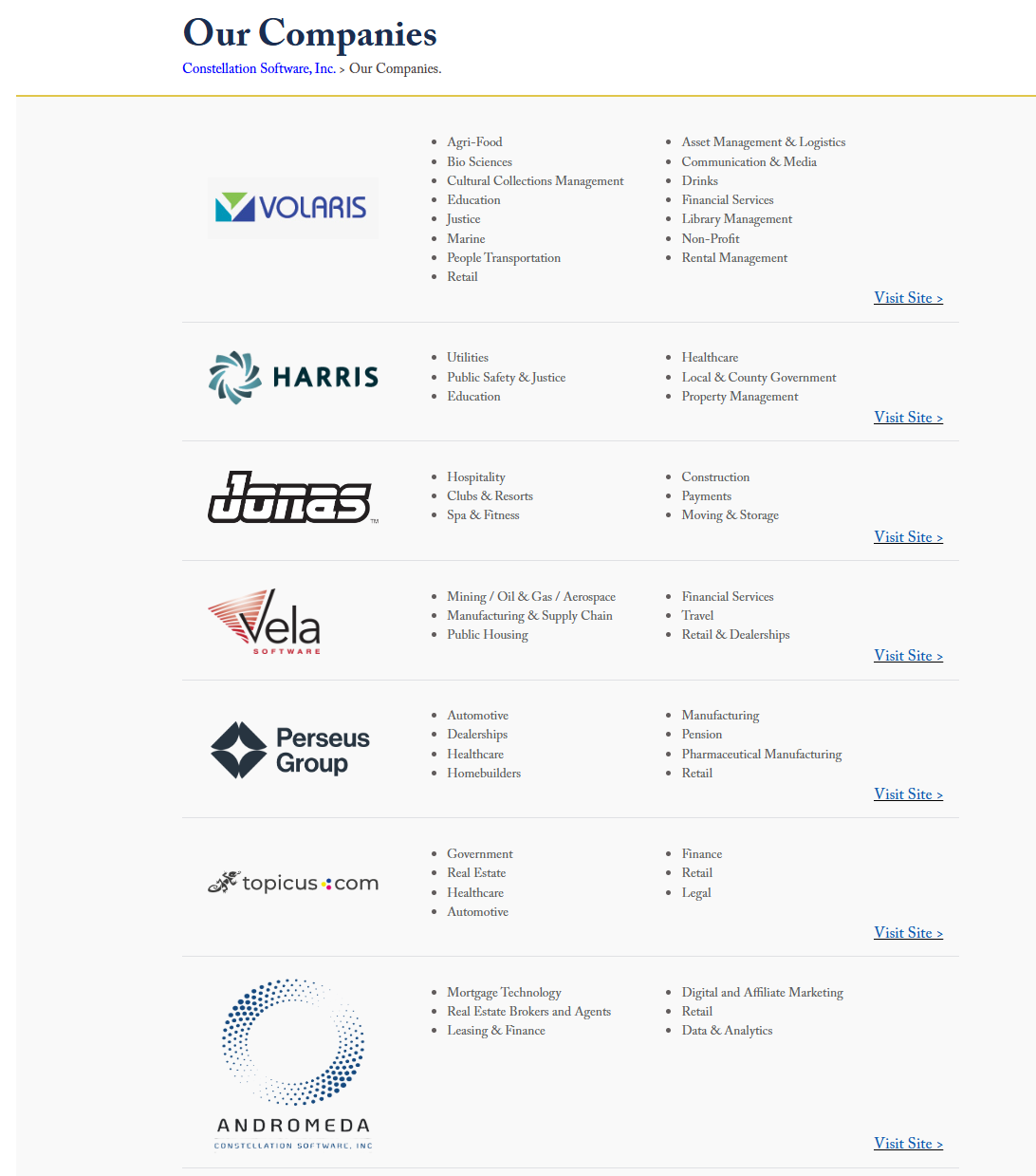

5. Constellation Software’s structure + subsidiaries

So, now we are going to do the tricky thing, try and understand how Constellation’s structure actually really works. As you can see in the picture below, CSU has split themselves into 6 operating groups (excluding themselves).

5.1 The operating groups

The above picture is a bit old, but it does give you a good grasp of how they layers work. I’ll explain in short what all 6 of these operating groups do and what their key focus is. All of these, especially Topicus and Lumine deserve their whole separate deep dives, but I’m not gonna be doing that. I will cover Topicus and Lumine a bit more in-depth in this chapter, but I will still keep it high-level.

Here is a high-level overview of the main focus of all the operating groups.:

Volaris

Volaris focuses heavily on international expansion and diverse vertical markets. They are known for being the “generalist” wing of Constellation, acquiring businesses across more than 40 different verticals.

Their key focus is on: Agri-food, Education, Financial Services, and Asset Management.

Harris

Harris is the oldest operating group and originally focused on the Public Sector. Over time, it has expanded significantly into mission-critical infrastructure software.

Their key focus is on: Utilities (Electricity/Water/Gas billing), Healthcare (Hospitals and large physician practices), and Local Government/Schools.

Jonas

Jonas initially built its reputation in the Club and Leisure markets but has since diversified into over 25 different verticals.

Their key focus is on: Fitness & Sports, Attractions (Theme Parks), Construction, and Foodservice.

Vela

Vela is primarily focused on industrial and asset-heavy sectors. Their portfolio consists of software that helps manage physical resources, manufacturing, and complex global logistics.

Their key focus is on:: Energy (Oil & Gas), Mining, Metals, Manufacturing, and Distribution.

Perseus

Perseus targets businesses that are industry leaders in specialized sectors, often focusing on markets with high stability and long-term customer relationships.

Their key focus is on: Real Estate (MoxiWorks), Mortgage (Optimal Blue), Pulp & Paper, and Finance/Insurance.

Andromeda belongs here with Perseus. Andromeda is not a separate operating group. It remains an operating unit within the Perseus Operating Group for now. They do have their own branding and a distinct mission and focus. Andromeda is particularly active in the mortgage technology and financial services sector.

Topicus

Topicus is unique because it was spun off as its own publicly traded entity in 2021. Its primary focus is the European market, specifically the Netherlands, Germany, and France.

Their key focus is on: Public Health, Social Services, Education, and Financial Services within Europe.

5.2 Why did they do these splits?

Constellation Software’s decision to “split” or spin off certain groups like Topicus and Lumine into separate public companies is a strategic move, and it’s designed to solve the the rapid expansion and the accompanying troubles that came with it.

As Constellation grew, it became harder to maintain high returns on these increasing larger sums of capital. The splits are a way to “reset” the clock and try to maintain their growth engine.

As the they kept buying more and more VMS-businesses, it became impossible for everything to be run and/or approved centrally. By creating separate operating groups, Constellation pushed decision-making closer to operating levels. Each operating group can run its own portfolio of businesses, make smaller acquisition decisions, and allocate capital without constantly going back to head office. This lets the company do many acquisitions in parallel and deploy capital much faster.

The structure also helps preserve the autonomy of the companies Constellation buys. Most acquired businesses are left largely independent, which keeps founders and managers motivated and reduces the risk of damaging customer relationships. The operating groups act as a light governance layer rather than a heavy central bureaucracy.

Another reason is capital allocation discipline. Operating groups effectively compete for capital, with head office allocating funds to the opportunities that offer the best returns. This creates an internal market for capital and reinforces Constellation’s focus on return on investment.

Finally, the split makes the organization manageable at scale. Each operating group is like a smaller version of Constellation itself, with its own leadership and acquisition capability. Spinning off a group also gave the managers an opportunity to take a direct stake in their own operating group. Their bonuses are tied specifically to the performance of their own group, rather than ‘‘mother’’ company where their individual impact might feel diluted and meaningless.

5.3 Topicus.com

So, we have to dive a bit deeper into both Topicus and Lumine. However, I will still keep it very high level, as both these companies kind of require their own deep dive, but that’s not what this CSU deep dive is about.

In early 2021, CSU spun off its European subsidiary TSS (Total Specific Solutions) and merged it with another Dutch company (Topicus B.V.) to create Topicus.com.

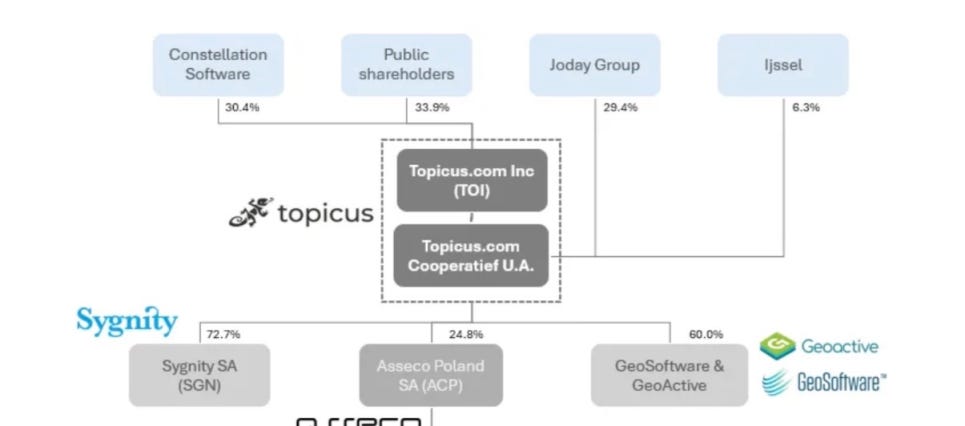

CSU has a 30.35% fully-diluted interest in Topicus.

Despite not owning a majority of the common shares, CSU holds a “Super Voting Share.” This gives CSU significant influence over the company’s board and strategic direction.

The ownership is split between CSU, public shareholders, and the original founders of the Dutch Topicus (through an entity called Joday). CSI consolidates Topicus in its financial statements, meaning Topicus is still a key part of the CSU empire.

Topicus is almost exclusively focused on Europe. They capitalize on European fragmentation, different languages, local regulations, and tax laws make it harder for "Big Tech" to compete, creating "moats" around small, local software providers.

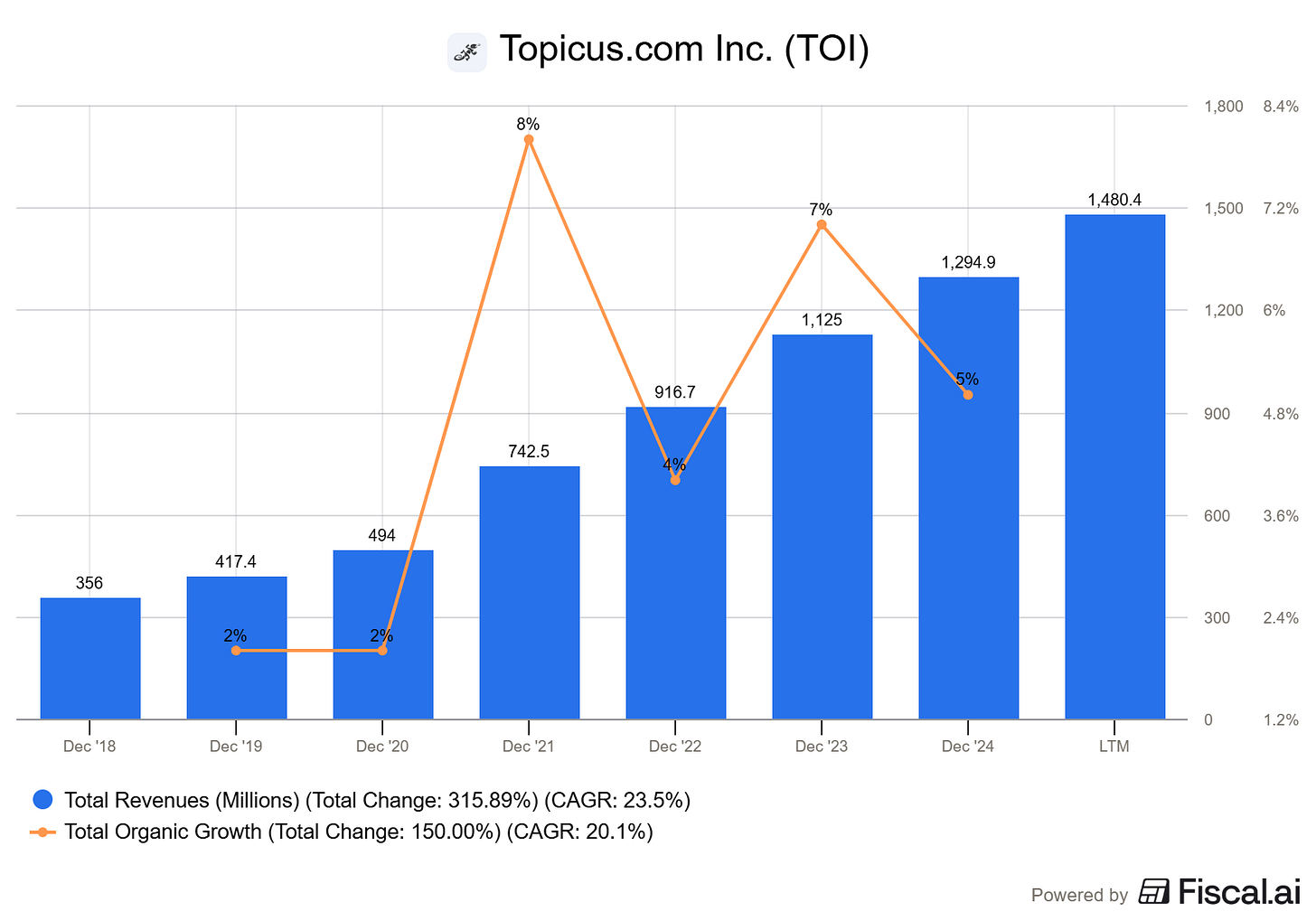

Topicus has delivered consistent double-digit revenue growth in the past quarters, of which about 3%-5% is organic growth, and the rest is revenue growth trough acquisitions. Revenue grew from ~€500M in 2020 to over €1.3B by 2024, continuing to climb in 2025. LTM sits at almost €1.5B.

In 2025 alone, they deployed over €700M in capital, nearly matching their total deployment from the first three years combined. They have grown from roughly 4,000 employees at IPO to over 8,000 today, doubling the size of the business in roughly four years

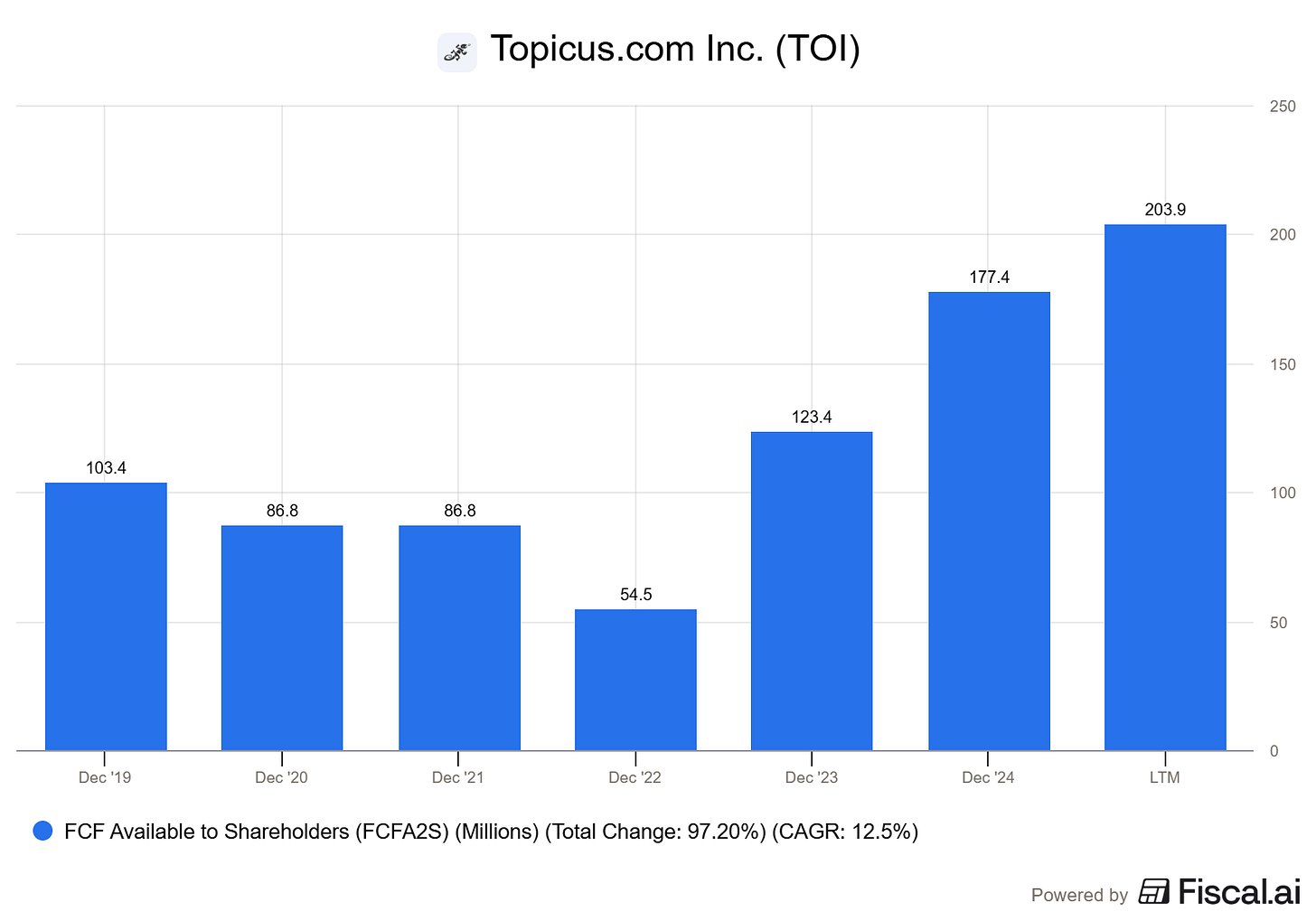

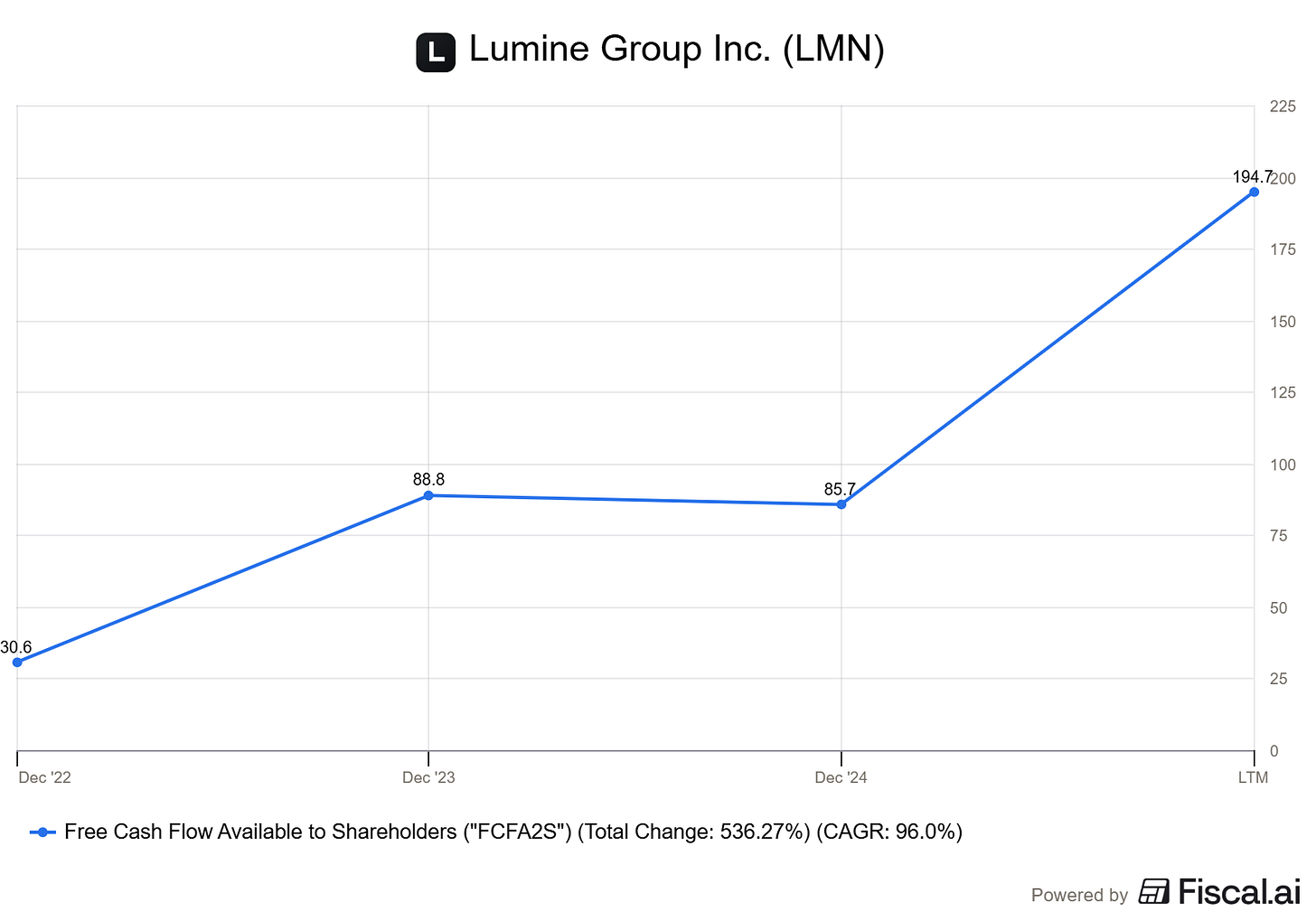

FCFA2S almost doubled since 2019, to about €200M LTM.

5.4 Lumine

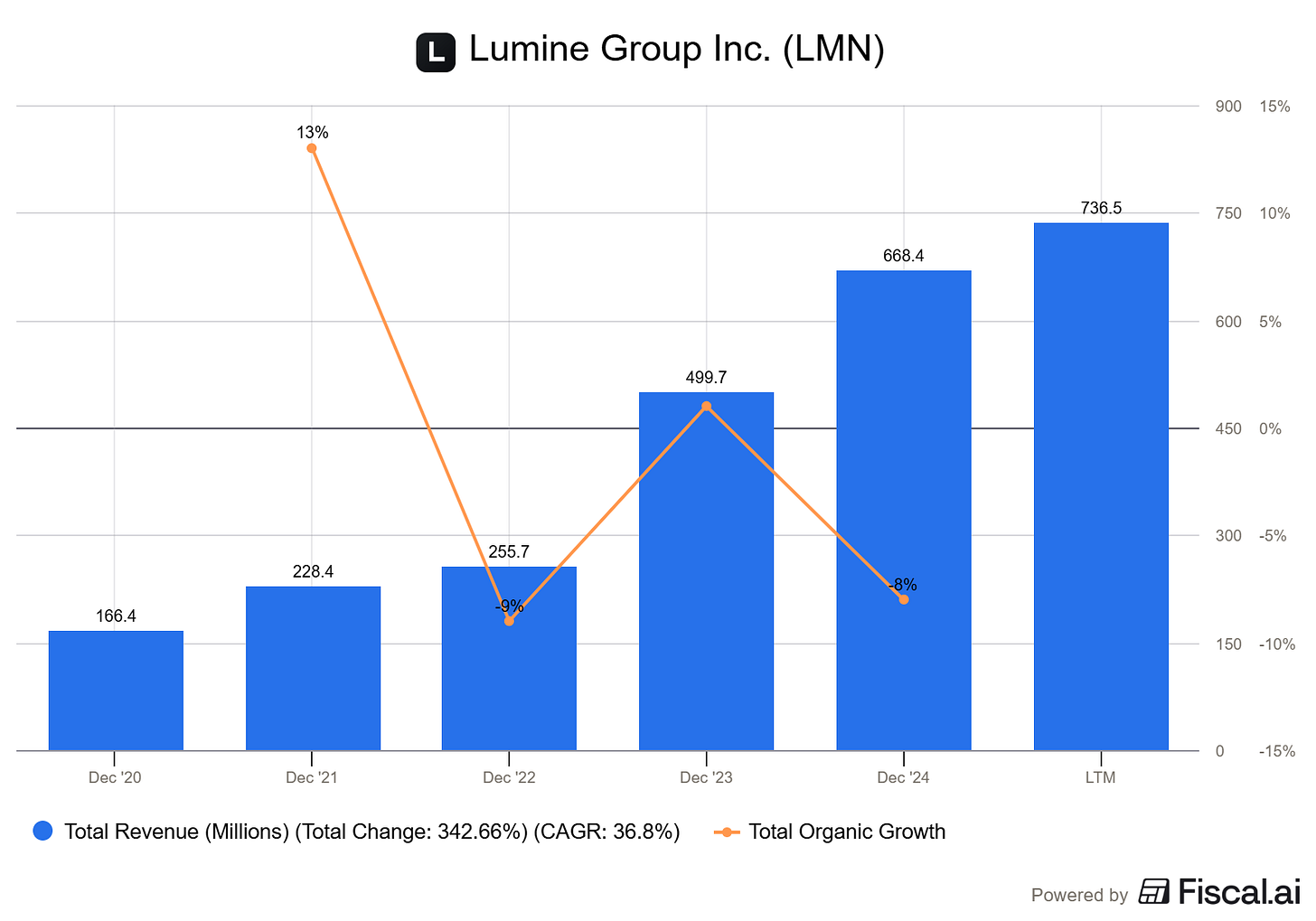

Lumine Group is the second major spin-off from the Constellation Software ecosystem. Lumine is primarily focused on Communications and Media. Lumine was born out of the Volaris Group. Lumine specializes in complex corporate carve-outs. They often buy "orphaned" divisions from giant conglomerates (like Nokia, Ericsson, or Synchronoss) that no longer want to manage a specific software niche.

The spin-off was triggered by the acquisition of WideOrbit, a major U.S. media software firm. To fund the deal and provide a "currency" for future large-scale media acquisitions, CSI carved Lumine out into its own public entity.

Lumine has a complex capital structure where CSI holds Preferred Shares and a Super-Voting Share, allowing them to maintain control and consolidate Lumine’s results while letting Lumine operate independently.

Unlike Topicus, which has very high maintenance/subscription ratios, Lumine deals with more complex systems. This leads to higher initial professional services revenue as they install and customize software for giant telcos. Lumine is deploying capital faster than Topicus did in its early years, specifically targeting larger "platform" deals in the $100M+ range

Revenue jumped from ~$400M pre-IPO to over $1B (LTM) by early 2026, largely due to the WideOrbit merger and subsequent "carve-out" deals. Only a fraction of that is organic growth, which is low but positive around 1%-2%.

FCFA2S grew over 200% YoY in mid-2025 as the company "cleaned up" the margins of its newly acquired businesses.

6. How does CSU make money?

If you look at CSU in the most simplistic way, it may seem CSU only has one growth strategy: owning and operating vertical-market software companies that throw off recurring cash flow. Everything else is a way of growing or compounding that cash flow.

But it’s a bit more complicated than that, so let’s take a look at the different growth engines we can distinct.

6.1 Acquisitions

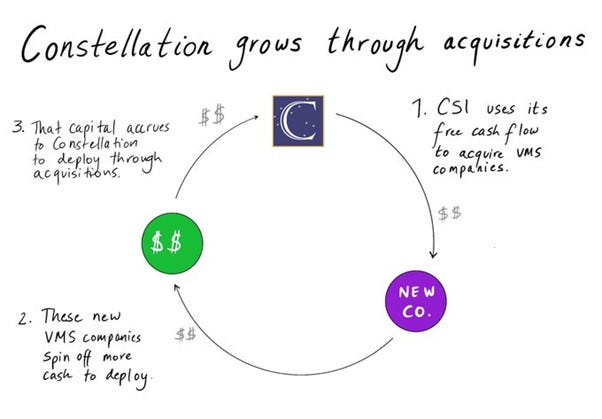

So, the first one is the most obvious one, and the one CSU is most-known for: doing acquisitions. We are not gonna go into what companies CSU buys again and how it’s done, but here’s briefly how this process turns into the cash machine they are right now.

As we discussed, CSU buys small, niche software companies at relatively low multiples, usually from founders who want liquidity but don’t want their business to be flipped or stripped. Because the software is vertical-specific and sticky, the cash flows are very predictable are reliable.

CSU does not rely on cost-cutting or aggressive synergies; instead, it expects the acquired business to keep generating cash at roughly the same or slightly better margins. The key is that CSU can reinvest that cash into more acquisitions at similarly attractive returns. This is the main compounding loop:

Buy → Generate cash → Buy again.

This has worked perfectly in the last years, therefore the stellar returns. Right now there are some concerns that there aren’t enough opportunities for CSU to keep using the FCF to generate. So eventually they might start doing acquisitions outside of VMS, or bigger acquisitions like they have in the past years, or find different ways to return the FCF to shareholders. That would require them to step out of their comfort zone.

The thing is, CSU is not really a big fan of specials dividends or buybacks. I will discuss this more in-depth in the ‘‘Financials’’ chapter. So the primary focus is still on deploying that cash, albeit at lower hurdle rates or maybe through different markets (which is not yet happening).

6.2 Organic growth

The second key driver for growth is ‘‘organic growth’’. This basically comes from price increases, maintenance fees, upselling additional modules, and occasionally selling to new customers within the same niche.

CSU is very disciplined here: they prefer slow, durable growth over risky expansion. Even low single-digit organic growth matters because it compounds on a large and very stable revenue base.

I will talk more on organic growth and growth numbers in the ‘‘Financials chapter’’.

6.3 Efficiency improvements

The third driver, and this one is a bit more philosophical and lesser-known: margin and capital efficiency improvements.

Over time, CSU improves how businesses are run by sharing best practices across the whole portfolio: pricing discipline, capital allocation, incentive systems, and operating metrics. They have a ton of data and experience on what works and does not. That is very valuable information which is widely shared within the whole CSU portfolio.

This doesn’t always show up as margin expansion, but it increases free cash flow per dollar of revenue. Higher free cash flow means more capital available for reinvestment at high returns.

6.4 Internal reinvestment within acquired businesses

Some cash is reinvested back into the same business (new features, bolt-on acquisitions, small tuck-ins). These reinvestments often earn very high returns because they are done within an existing customer base and niche where CSU already has deep knowledge.

7. Competitive advantage

Defining CSU’s competitive advantage is not super easy to do. Purely looking at the business and it’s model one could think? Anyone can do this.

In the end, what they do is not necessarily special or very complex.

Mark Leonard ones famously said:

The barrier to starting a 'conglomerate of vertical market software businesses' is pretty much a cheque book and a telephone."

What he means by this; the strategy is no secret and litteraly anyone can do it. In essence it sounds very very simple. But execution and doing it well, that’s the difficult part.

And here I believe we reach the crucial point in their competitive advantage; the execution.

So what are the key foundations that led to their succes and competitive advantage?

In my opinion those points are: culture, decentralization and data.

7.1 The Culture

We discussed the culture in a previous chapter, so I’m not gonna repeat what makes their culture so special. Just to summarize, it’s a mix of business principles, focusing on core values and providing a safe haven for their companies.

But what makes the culture even more different from others, besides the forementioned points is:

Discipline.

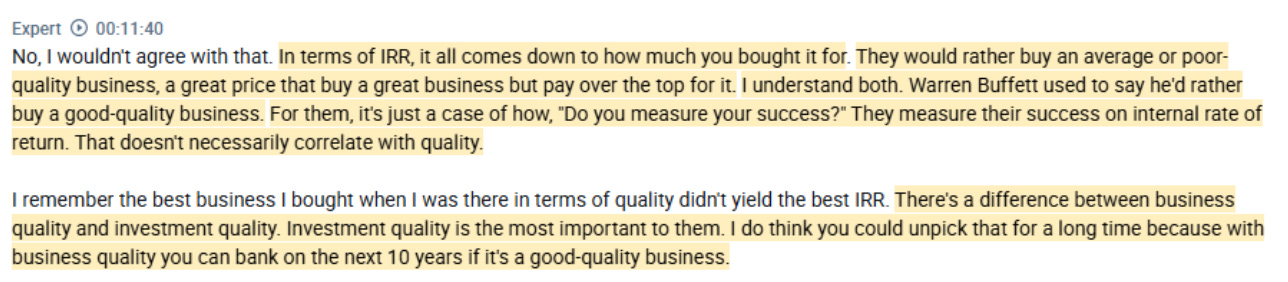

CSU is almost fanatical about its IRR. They have historically maintained a “hurdle rate” (the minimum expected return) of around 20–25%.

A hurdle rate is the minimum return a company must expect to earn before it agrees to buy a business. Constellation Software uses this as a strict rule to ensure they only spend money on deals that will significantly grow their value, typically aiming for an IRR of about 20-25%. By sticking to this "high bar," they avoid overpaying for average companies and maintain the a disciplined approach.

And to them it’s very simple: If a deal doesn’t meet the math, they walk away. Most competitors get hungry for deals and overpay during booming times. CSU’s discipline ensures they only buy when the price makes sense for long-term compounding.

CSU focusses mostly on IRR, and not just primarily on the quality of the company.

To quote Speedwell Research recent X post on this ( the real quote is by a former CSU M&A director:

“They would rather buy an average or poor-quality business, at a great price than buy a great business but pay over the top for it. That doesn’t necessarily correlate with quality. Investment quality is most important to them.”

CSU has an internal market for capital where operating groups compete for funding based on expected returns. Over time, this selects for managers who are good investors, not just operators. Bad capital allocation gets punished quietly; good allocation gets more capital

7.2 Decentralization

Something else that makes them unique, is how they have managed the decentralization process. A lot of companies really struggle with actually being ‘‘lean’’, and are usually just claiming they are. To give you an example: The head office has fewer than 20 people, while the company owns over 1,000 businesses.

Just take a look at the whole web of all the companies CSU owns:

If this doesn’t look like a constellation, I don't know what does.

CSU believes that small teams are more motivated and efficient. If a business unit gets too large (usually around 100+ employees), they often split it into two smaller units to keep the culture agile and focused on the customer rather than corporate politics

They have mastered this decentralization process over the years, and this has also acted as a growth driver. Without this decentralized web, they would have never managed to keep their IRR and growth rates this high.

7.3 Data

CSU has built a massive internal dataset across thousands of acquisitions and operating businesses. Because this data spans decades and hundreds of cycles, CSU can price risk far better than competitors. When they evaluate a new acquisition, they are not guessing. They can compare it to dozens of similar businesses they already own and know.

This data advantage compounds over time. Every acquisition adds another data point, which improves future decision-making. Private Equity firms often lose this learning because deals are sold and teams rotate; CSU never sells and keeps institutional memory.

Another subtle advantage is that CSU uses data to know what not to do. They have clear evidence of which verticals, pricing behaviors, or integration approaches destroy value. Avoiding mistakes is a huge competitive edge in compounding businesses.

7.4. Reputation.

Constellation software has built it’s reputation over the span of many many years and acquisitions. This is something that is often forgotten: it isn’t all about the numbers. This is especially true for the VMS companies that CSU has, or wants to have, in its portfolio.

A large part of it comes down to trust, as well as the reliability of the software and the services provided. These are things that take years to build. CSU has worked incredibly hard their image for many years. The reputation they have built cannot simply be replicated.

8. Competitors + Copycats

In recent years, there were significant concerns about potential competitors disrupting Constellation Software’s (CSU) business model. However, the peak of these concerns seems to be behind us now.

As it turns out, what CSU does, isn’t quite as easy as it looks. In theory, anyone with a bag of money and a phone book could be a competitor, but in practice, the execution is much more difficult.

Something that is often overlooked is that money alone isn’t enough. You still have to map out the entire market, establish contact with the companies, earn their trust, and ultimately convince the owner to be acquired.

In this process, it’s not just about the capital; factors like trust, track record, and the future of the company after the sale play a crucial role. But we have discussed these points before.

We can identify a couple of competitors, that are operating in the same space as CSU. I will go over the most important ones below.

8.1 Roper Technologies

Roper has a similar strategy as CSU, but they usually aim for bigger companies than CSU does. Roper focuses on much larger acquisitions (deals worth hundreds of millions or billions) rather than CSU’s approach, with sometimes just a couple of millions per acquisition. Roper also tends to centralize more functions over time, whereas CSU remains heavily decentralized.

8.2 Halma

One that is a bit lesser known is Halma. Halma is a UK-based serial acquirer focused on safety, health, and environmental technology.

Halma buys companies that make physical products (hardware/sensors), not just software. While they share the "decentralized" philosophy, managing physical inventory and global supply chains is a a completely different business than buying VMS companies.

8.3 Tyler Technologies

Tyler technologies is quite a big boy too. They are a large acquirer focused specifically on the Public Sector (local government, courts, schools).

Unlike CSU, which is vertically agnostic (buying everything from funeral home software to marina management), Tyler is a "pure play." They focus on dominating one single vertical rather than diversifying across hundreds

8.4 The big boys

When CSU tries to buy a larger software company in a specific niche, they often run into companies like Oracle, SAP, or Salesforce. However, these companies are looking for synergies, they want to strip out the acquired company's staff, move the customers to their own cloud, and merge the product into their "suite."

CSU doesn't "break" the acquired company. They keep the original brand, the original staff, and the original office. For a small software company with 20 loyal employees, being bought by Oracle often means being "absorbed and deleted," while being bought by CSU means "business as usual, but with a better bank

8.5 Thoughts on competitors

While there are quite a few names that compete with CSU in their space, I would say that right now, none of them come close to what CSU does.. It’s either that, or they have a more specific focus or approach to how they operate.

Each of these competitors have something they can use to challenge CSU. They all have their own strengths, their own focus, or their own niche.

But most importantly: no one does it as well as CSU does.

CSU is miles ahead, thanks to years of experience. Thanks to the data. And thanks to the vision established by Mark Leonard.

Should we close our eyes to the competition? No, not at all.

But for now, I believe CSU is still in a strong position, without any real major disruptors on the horizon.

9. Risks and Headwinds

We have covered some of the concerns that are currently pushing the price down in Chapter 2. In this chapter I will address the second part, the AI fears a bit more.

Just to sum it up with we have discussed in Chapter 2:, Mark Leonard stepping down and the struggle for CSU to continue to deploy their cash at a high IRR. On top of that: the whole SaaS sector is heavily sold off due to AI fears. Valuation might have been a bit too high as well, so some of this sell-off is absolutely warranted.

Fundamentally, nothing has really changed in the past year. You might think it did, by simply look at the share price, but a lot of that seems narrative driven. They are put in the naughty corner with all of the other SaaS companies, but CSU is just fundamentally different.

People who worry most about AI tend to focus on what is technically possible. But in for CSU what matters far more is what organizations are willing and able to change.

Across CSU’s businesses, you see pretty much the same story over and over. The software tends to be absolutely mission-critical, baked into day-to-day operations, local rules, and regulatory processes, and in many cases it’s been customized and tweaked for years.

In practice, that means a utility, municipality, court system, airport, or even a country club is not suddenly going to “vibe-code” a replacement just because AI technically could handle parts of it.

These buyers aren’t really shopping for the flashiest tech or the cheapest option; they care far more about not breaking anything and not putting their own jobs at risk. Most of the business are not flash and highly innovative, so even when better technology exists, actual adoption usually trails by many years.

Because of that, even if AI can do more of what these systems do in theory, the regulatory, organizational, and human factor in CSU’s verticals likely pushes any real disruption far into the future.

At the same time, even as AI becomes more agentic and probabilistic, most of CSU’s customers still need a single, authoritative record of things like transactions, billing, permits, cases, or memberships, along with a system that auditors, regulators, and courts are comfortable with and a stable database that can be inspected and defended.

But there’s risk as well. I believe a more real threat to the business is in their Professional Services segment. If AI makes implementation work easier, shortens customization projects, and speeds up integrations, CSU could end up earning less services revenue per customer, which might slow top-line growth and shift the mix more toward recurring software revenue.

And even if the core software remains indispensable, there’s a plausible longer-term risk that more of the perceived value moves to AI layers on top, that pricing power drifts “up the stack,” and that CSU’s products start to look more like low-growth infrastructure. That could mean slower revenue growth, lower valuation multiples, and more pricing pressure over time.

But you can also look at this from a different angle: CSU’s largest cost base isn’t its software, but its people. If AI can take on parts of development work, lighten the support load, speed up implementations, and improve product quality without requiring a larger engineering workforce, CSU could keep its pricing power while lowering internal costs and ultimately expanding margins, even if top-line growth moderates. Its decentralized structure also helps here, as each operating unit can test and adopt AI in its own way rather than forcing a single company-wide approach.

All these AI fears and threats also don’t show up in the numbers (yet). While growth slows down just a bit, the numbers don’t reflect a doom-scenario. Let’s dive into it, and you’ll see what I’m talking about.

10. Financials + numbers

In this chapter we will look into the key financial aspects of CSU. Let’s first take a look at the revenue numbers.

10.1 Revenue

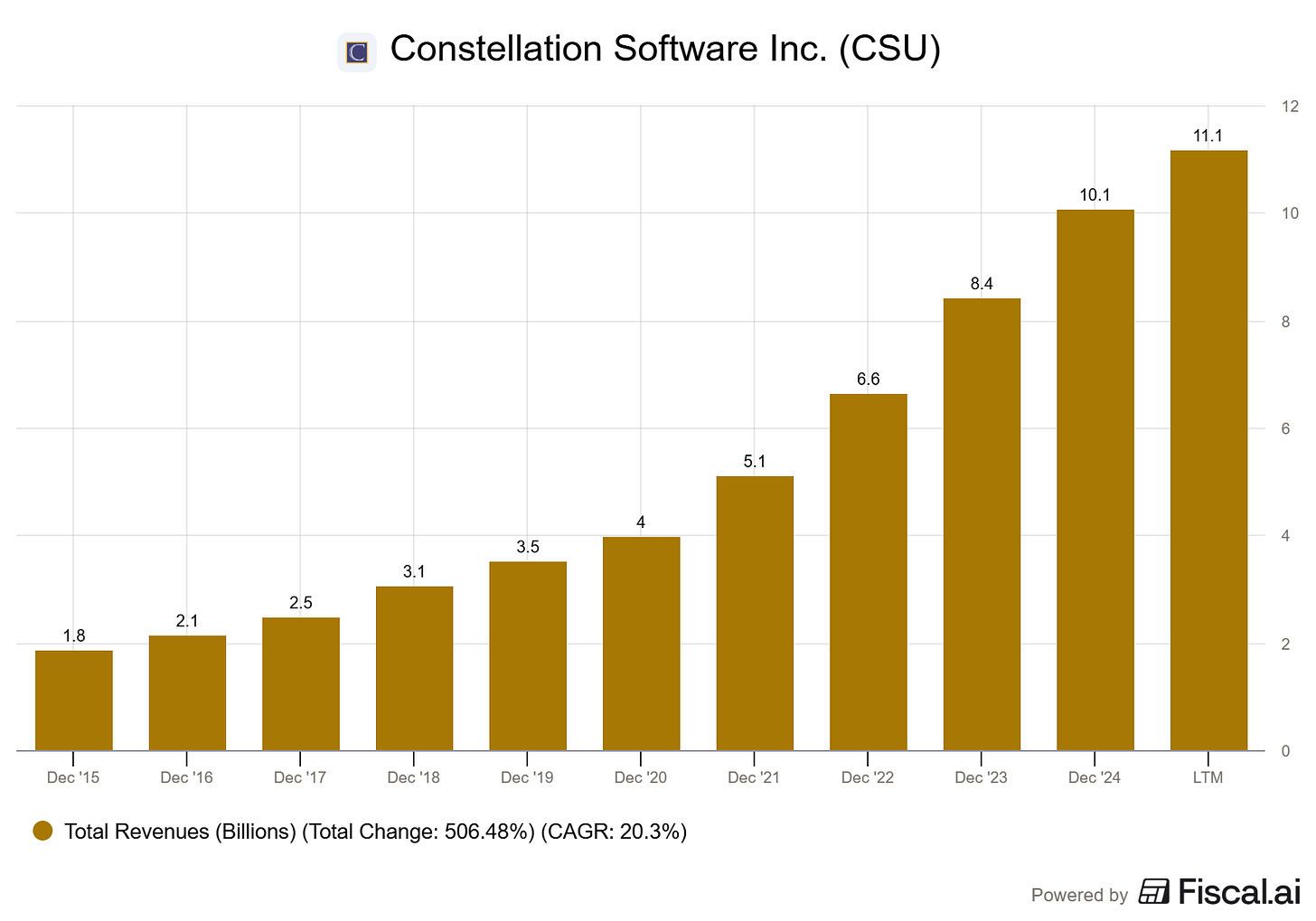

CSU’s revenue growth is a thing of beauty in my eyes. This is what true compounding looks like. They have increased their revenue from $1.8B in 2025, to $11.1B for the LTM.

Over the last 10 years, they’ve had a 20%+ revenue CAGR. As we discussed before, it will be continuously harder for CSU to keep that level of revenue growth. Since they have scaled so hard, the FCF the generate grows larger and larger, and it’s getting more difficult to deploy it all at a high IRR.

I think it’s wise to look at how this revenue was generated. We will make the distinction between maintenance revenue and organic growth.

Maintenance revenue is a category of money they collect, while organic growth is a measurement of how much that money is increasing in the businesses they already own.

10.1.1 Maintenance revenue

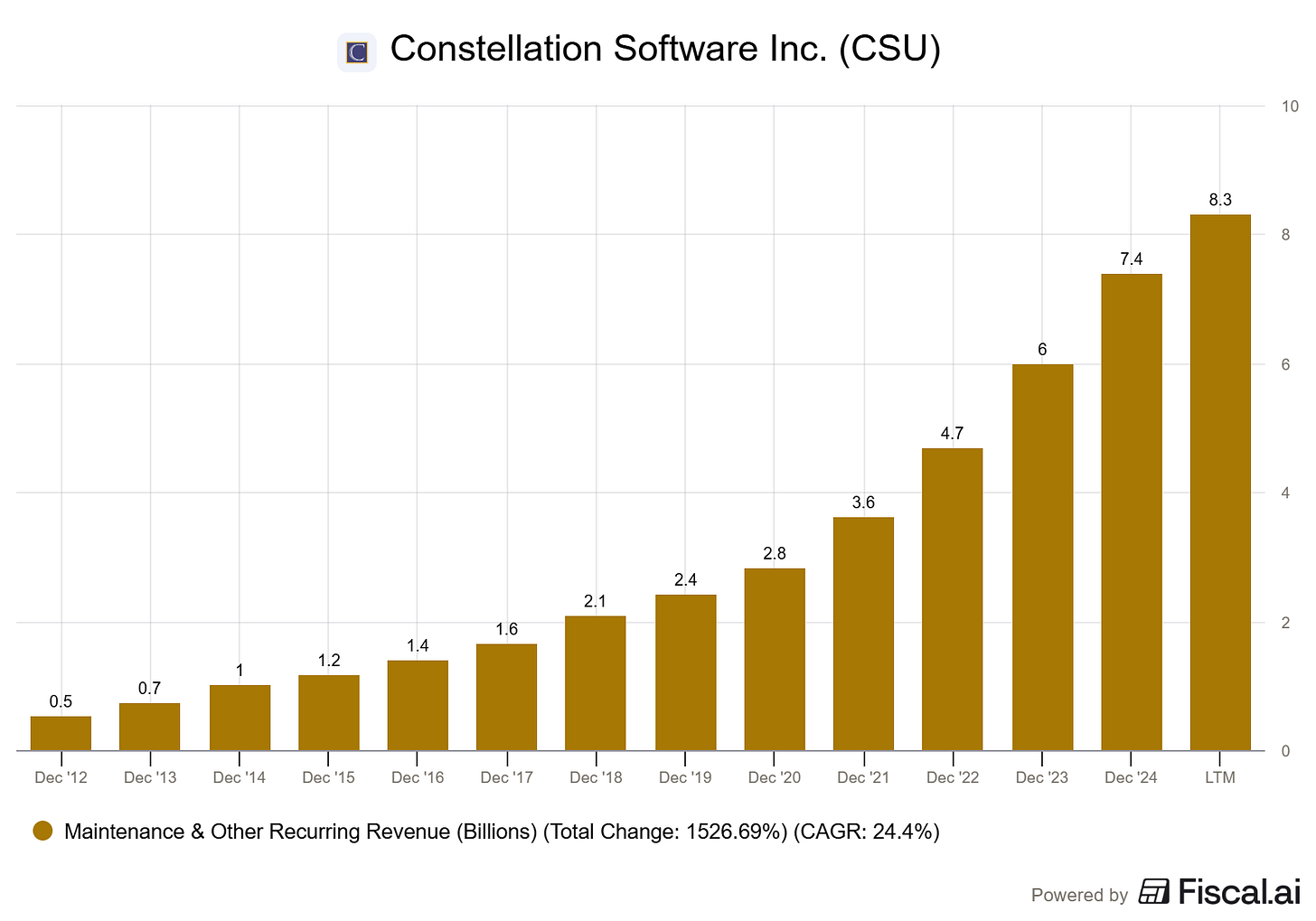

So this one might sound a bit weird: ‘‘maintenance revenue’’. But, this is actually the bread and butter for CSU. So what does it mean?

Maintenance revenue is the recurring fee customers pay every year to keep using the software, get updates, and receive technical support. So it’s not really the growth through acquisitions but rather the "fuel" that proves whether those acquisitions were actually good ones.

Mark Leonard believes that Net Maintenance Revenue is the single best indicator of a software company's value. If maintenance revenue is growing organically (even just by 1% or 2%), it means the software is still relevant and the customers are happy. If it starts to shrink, it’s a sign that the "moat" is leaking and customers are leaving.

Maintenance revenue is what creates most of the Free Cash Flow, so this a key one to watch.

Just like the total revenue, a thing of beauty. Steadily compounding at a 24.4% CAGR over the span of 10 years.

10.1.2 The other revenue streams:

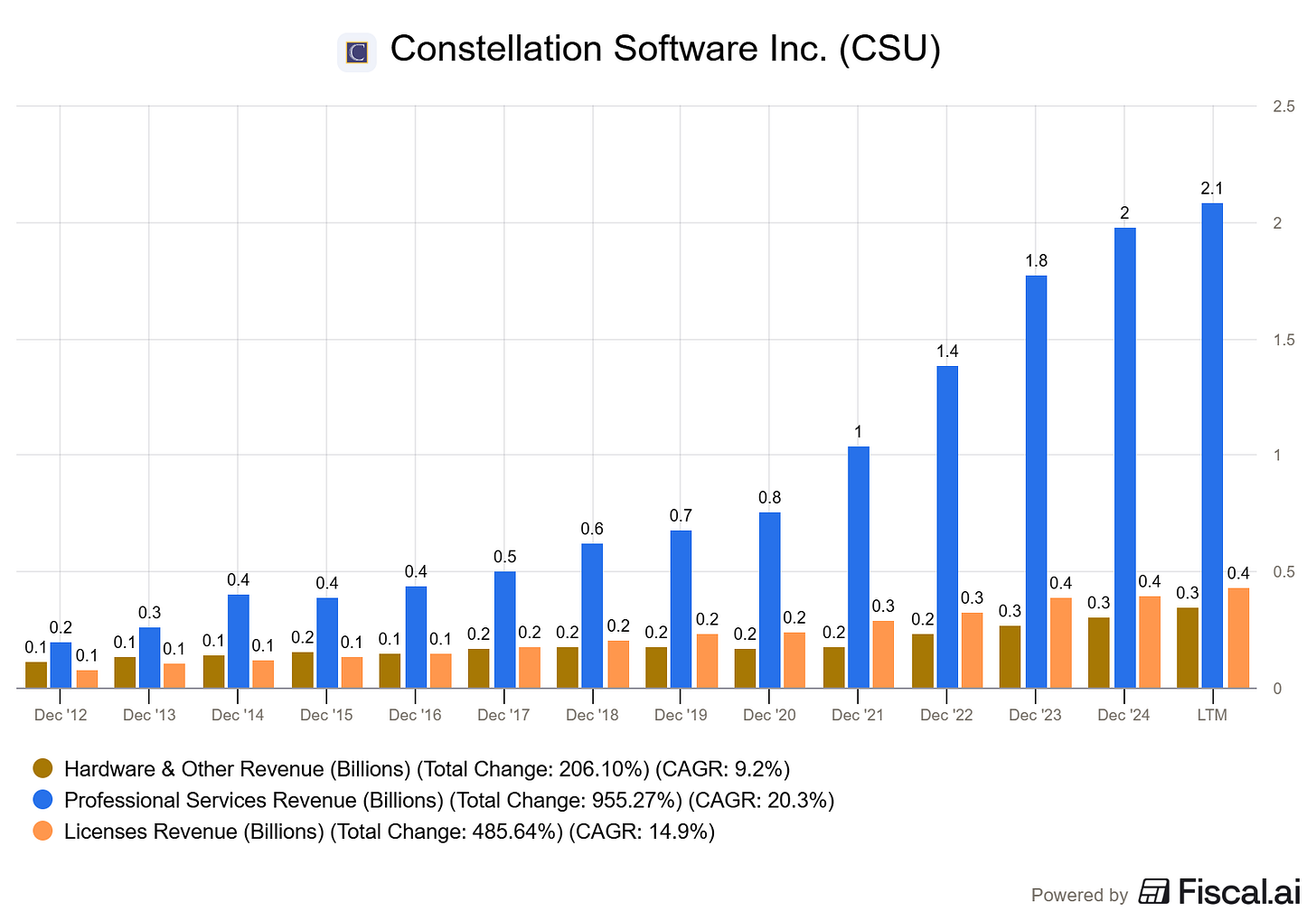

License Revenue

This is the one-time fee a customer pays to get the right to use the software, this is non-recurring. CSU often tries to convert these one-time licenses into recurring subscriptions (maintenance revenue) over time to make the business more stable

Professional Services Revenue

This covers fees for implementation, custom programming (tweaking the software to fit the client's specific needs), product training for staff, and consulting.

Even though this is technically one-time work, it is very important. The more "Professional Services" a customer buys, the more deeply the software is integrated into their business. This makes them much less likely to ever leave, in turn, reducing "churn".

Hardware and Other Revenue

Sometimes the software requires specific physical equipment to function. If they sell software for public transit, they might also sell the physical ticket scanners. If they sell software for a library, they might sell the barcode readers.

They generally only sell hardware because the software won't work without it, this is not their focus. They often have lower profit margins here compared to their software.

All three combined make up about 25% of CSU’s revenue. Not insignificant, but this is not the core focus of the company. Growth has been steady for most of these segments, although it can be quite lumpy from time to time.

10.2. Organic Growth

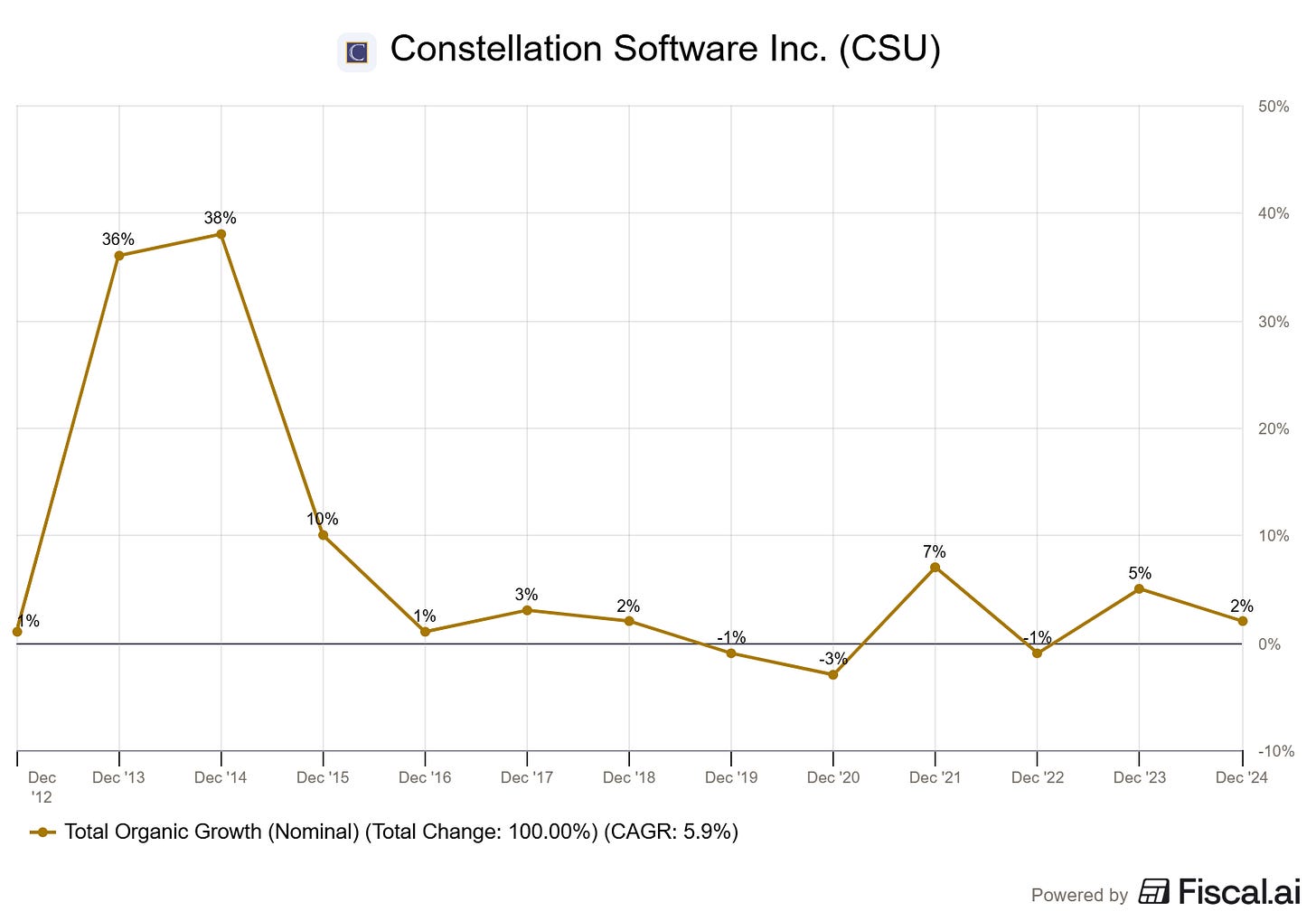

This is another key one that investors watch. The organic growth. Organic growth is the rate at which the company grows without including the revenue from new acquisitions. It tells you if the software companies CSI bought 5 years ago are still healthy or if they are shrinking

CSU’s organic growth is typically very low (often -3% to +5%). This is because they buy "mature" software that has already captured most of its market, so it’s not growing fast anymore.

The main drivers contributing to organic growth are:

Increasing annual fees by 3–5% (often tied to inflation). Because the software is “mission-critical,” customers stay and pay.

Selling an extra feature or “module” to a customer who has been with them for a decade.

Keeping “churn” (customers leaving) extremely low. If you keep everyone and raise prices slightly, you get positive organic growth.

10.3. Free Cash Flow Attributable to Shareholders

The best metric to look at CSU’s cashflow performance is FCFA2S. While still not perfect, it does give us the best insight into their cash flow.

Standard FCF is usually calculated as Operating Cash Flow - CapEx. However, Mark Leonard argued that this is too “optimistic” for a company like CSU.

FCFA2S is give a more honest look, because it subtracts several things that standard FCF often ignores:

Interest & Debt Payments: Standard FCF often ignores the cost of debt.

Lease Obligations: CSU treats office leases as a real cash drain that should be deducted.

Non-Controlling Interests (NCI): This is the big one. Since CSU owns companies like Topicus and Lumine (where they don’t own 100%), they subtract the portion of cash that belongs to those other partners.

Tax Reality: FCFA2S uses actual cash taxes paid, not just “accounting taxes,” which can be misleading due to high amortization.

And then there is the IRGA. Which stands for ‘‘Investor Rights and Governance Agreement’’.

This refers to the deal CSU made with the “Joday Group” of their European business, TSS, Topicus.

The IRGA has a big, often confusing impact on FCFA2S because of two things:

Under the IRGA, the minority owners have the right to sell their stake back to CSU at a price based on a formula. Every quarter, CSU has to guess what that stake is worth. If the business does well, the “value” of that liability goes up, and CSU records a charge (an expense).

This is a non-cash charge, but CSU includes it in the FCFA2S calculation to remain conservative. It can make the FCFA2S look lower than it actually is in “good” years because the business became more valuable.

When those minority partners actually decide to “cash out” parts of their ownership (which happens under the IRGA rules), that is a massive exit of cash.

FCFA2S accounts for these potential or actual payouts. It ensures that shareholders aren’t fooled into thinking CSU has $1 billion to spend on acquisitions if $200 million of that is actually “owed” to the TSS partners.

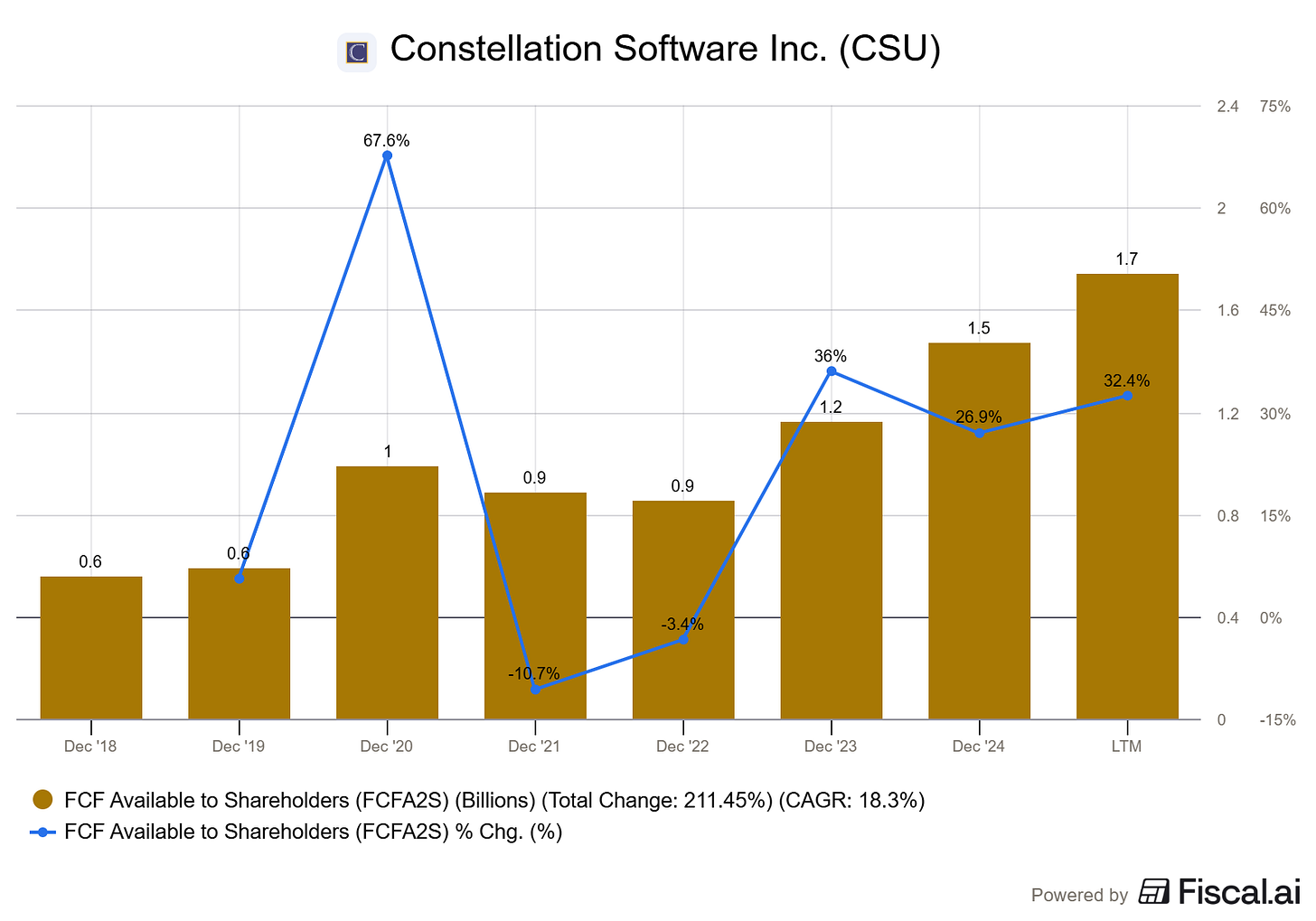

FCFA2S has been growing at a 18.3% CAGR over the past years. It can be a bit lumpy, because even though maintenance revenue is "recurring," the cash for it doesn't always arrive in a smooth line. There’s also Tax Timing and FX volatility that can impact the FCFA2S. But overall, the trend is up as you can see.

10.4 Operating Profit + Adjusted Ebitda

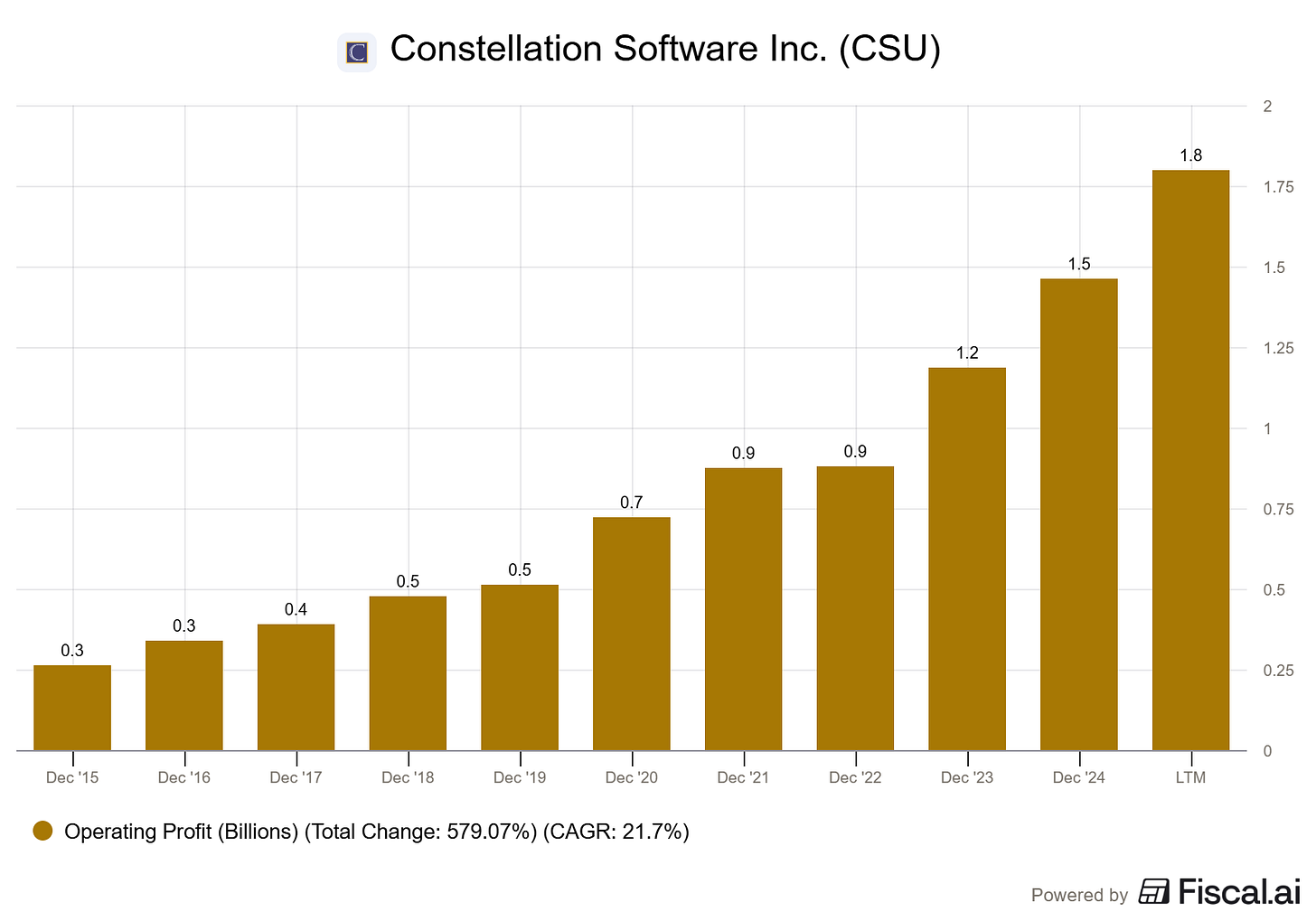

As we saw in the FCFA2S part, CSU is making a large profit. Their operating profit has grown at a 21.7% CAGR in the past decade.

Keep in mind, CSU’s operating profit looks lower than it actually is. Because they buy so many companies, they have massive non-cash amortization charges. This "punishes" the reported operating profit even though the cash is still in the bank.

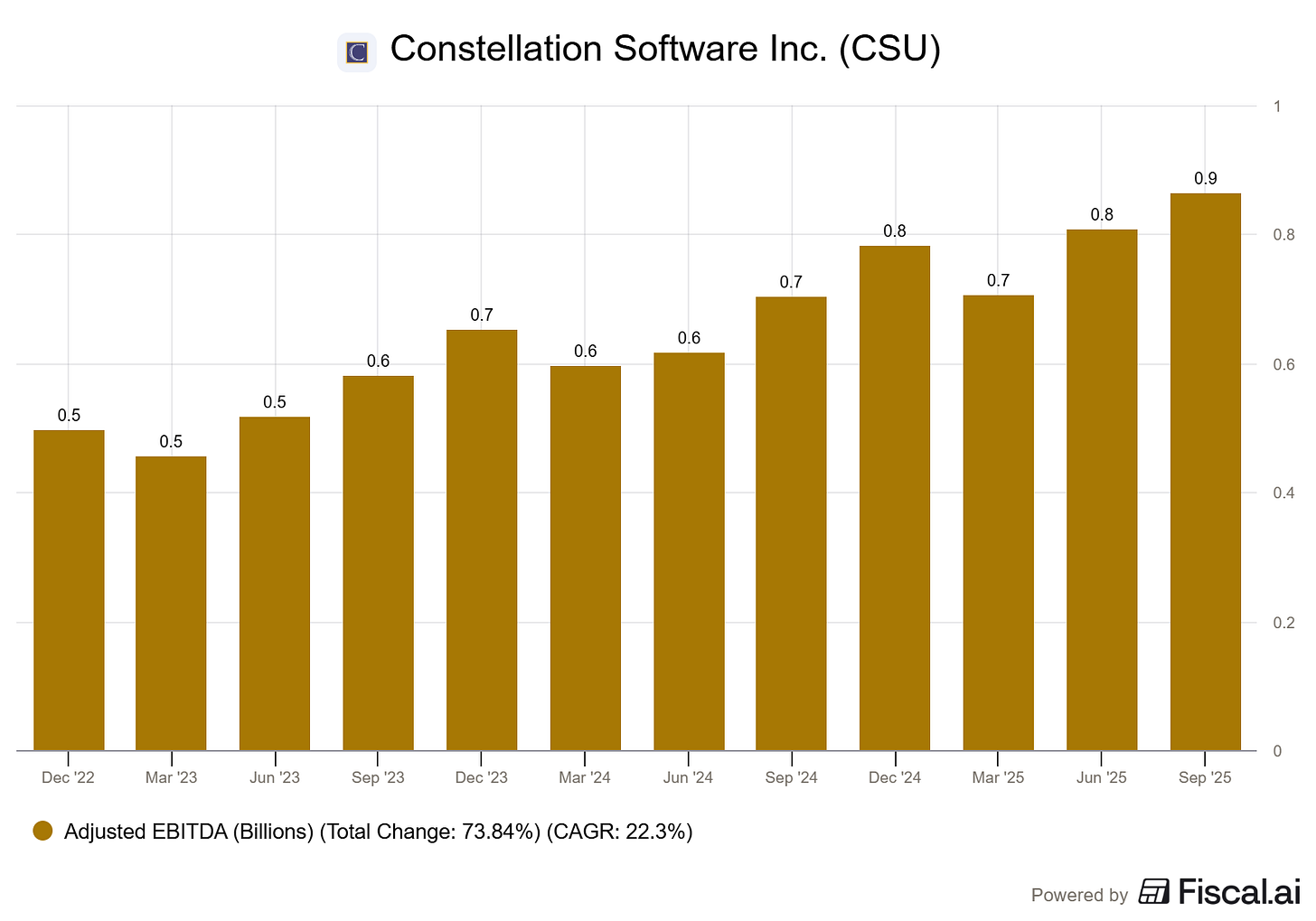

CSU prefers Adjusted EBITA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, and Amortization). This removes the acquisition-related "accounting noise" to show the true efficiency of their software businesses. The Adjusted Ebitda grows at a 22.3% CAGR as well in the past decade.

10.5 Shares Outstanding

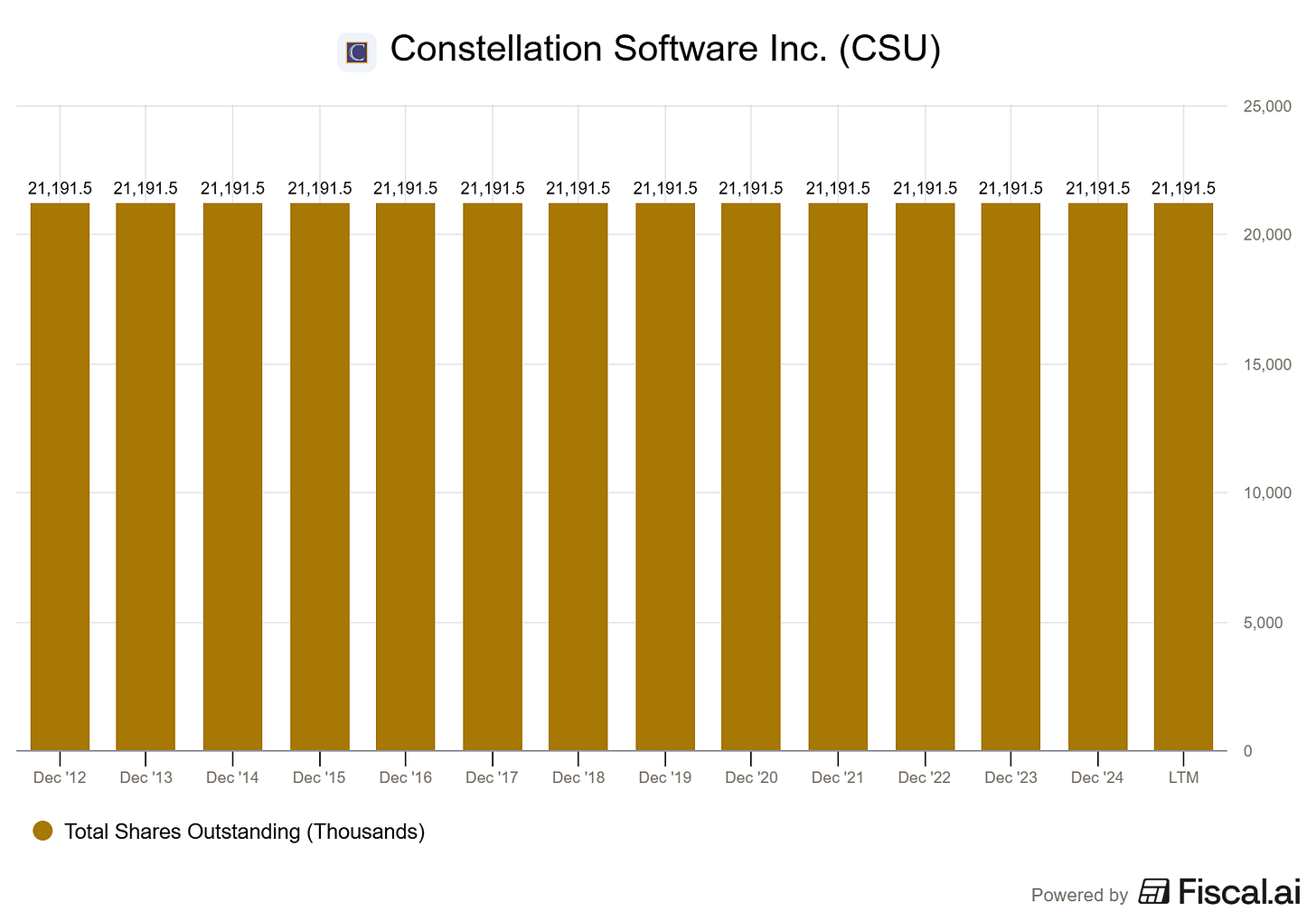

This might be the most boring chart you will ever see, but it is important nonetheless.

CSU, has NEVER diluted shareholders. And I doubt they ever will.

They have also never bought back any shares so far. And again, I doubt they ever will.

Mark Leonard covered this subject during many of his letters and in Q&A sessions at the yearly meetings (most important one being the 2018 one). Here are some of my favorite quotes of Mark on the matter:

"To the extent that we are able to buy back shares at a price that is less than intrinsic value, we are increasing the value of the remaining shares. However, we are doing so at the expense of the selling shareholders. I find it difficult to reconcile this with the idea of a partnership."

"I believe that a President/CEO’s job is to ensure that the stock price is 'fair'—not high, not low, but fair. If the stock price is significantly below intrinsic value, the CEO has a duty to inform shareholders so they don't sell their shares too cheaply. If the stock is significantly above intrinsic value, the CEO has a duty to inform potential buyers so they don't pay too much."

"The CEO and the board have more information about the company than the average shareholder. Using that information advantage to buy back shares from a partner who is less well-informed is, in my view, a questionable practice."

I really doubt they will ever change this stance, although I believe some shareholders really wouldn’t mind if that cash was spend on buybacks, at the right moment.

10.6 Dividend + Special dividend

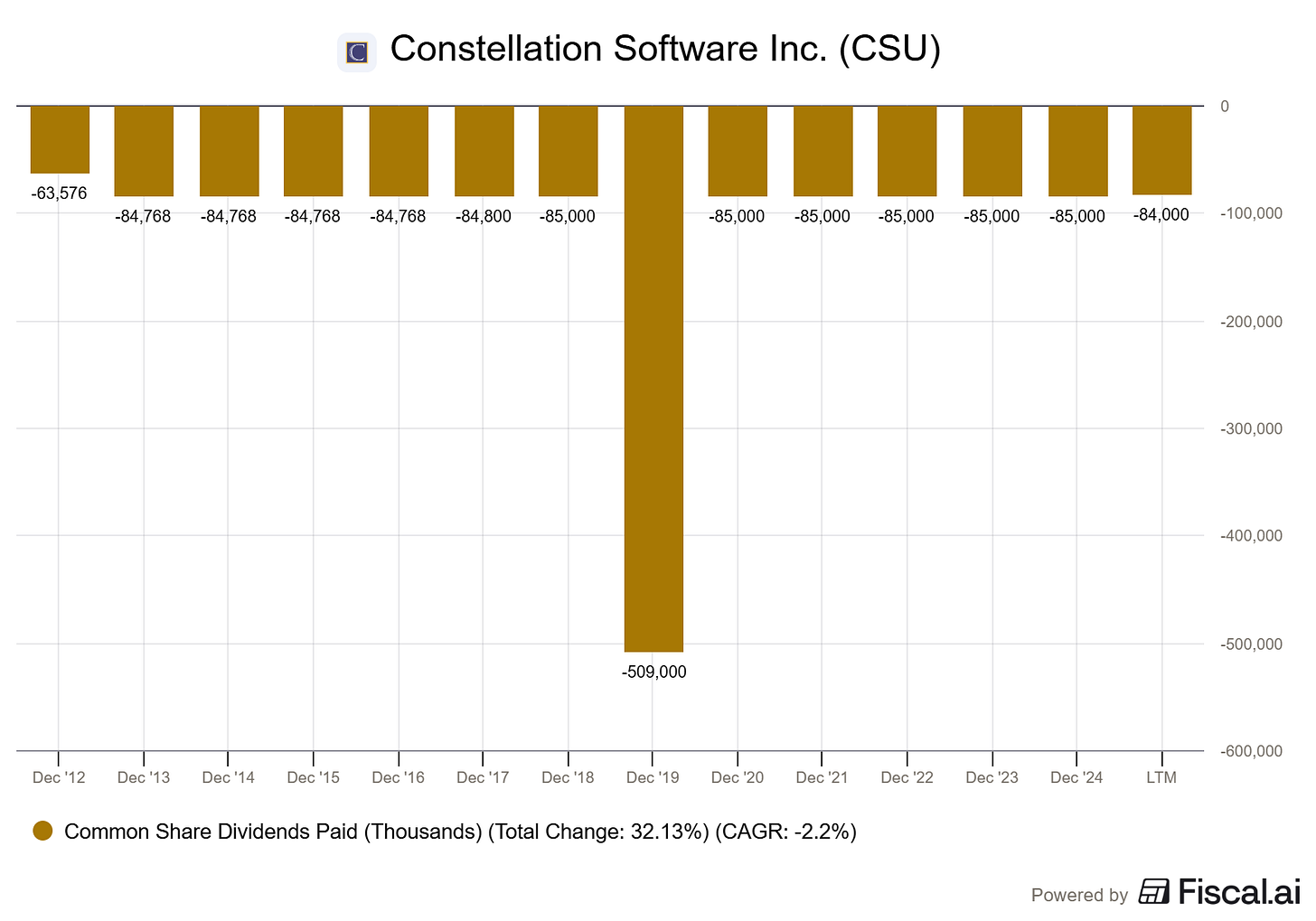

CSU does pay a very tiny dividend, they have dividend yield of about 0.2%. You might notice the large dividend payout in 2019, which was a one time thing. For over a decade, CSU has maintained a remarkably consistent but tiny dividend: $1.00 USD per share, every quarter.

In March 2019, CSU shocked everyone by declaring a $21.00 USD per share special dividend. While most investors did not complain, Mark Leonard was actually not happy.

Mark Leonard did not celebrate this $21 dividend. In fact, he characterized it as a sign of defeat.

“Perhaps dividends are perceived as a failure… but to my mind, they are less of a failure than sitting on excess cash.”

His logic was simple: If he were doing his job perfectly, he would have found $500M worth of great software companies to buy. Since he couldn’t, he felt he had to give the money back rather than let it rot in a bank account.

In 2021 Mark Leonard stated he would forever stop paying special dividends "in all but the most compelling circumstances’’.

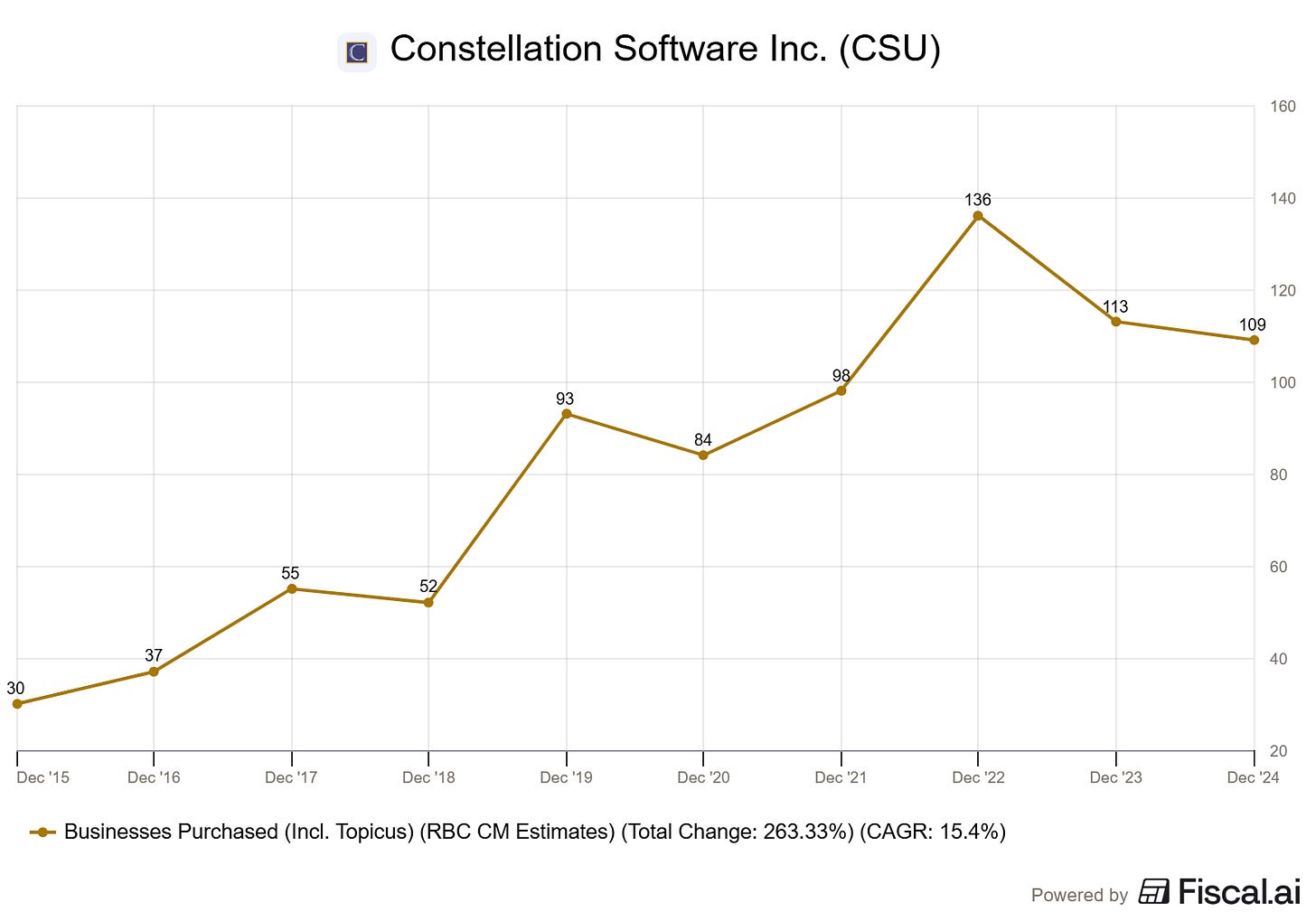

10.7 Business Purchased

This should not come as a surprise to you, but as CSU grew bigger and bigger, the amount of acquisitions they do increased over the year. Keep in mind, this also includes the purchases in subsidiaries like Topicus and Lumine.

As you can see, the amount of business purchased is a bit under pressure. This is mainly do to:

higher valuations in the VMS market

Large deals, with higher acquisition sizes

Market saturation in a couple of their segments

So, just looking at the sheer numbers of acquisitions doesn’t tell the whole story. Eventually it is all about the balance between capital employed and the expect IRR they get on these acquisitions.

Do you also want to make charts like this? with the below link you get a 15% discount on all your fiscal.ai subscriptions. The free software is also very good, so be sure to check it out

11. Valuation

There are a couple of ways to properly value CSU. The simplest method is by looking at the P/FCFA2S. This will give a good indication about how the share price is related to current cashflow and this is a widely used variation to look at CSU valuation.

On top of that, I have done a very extensive DCF-valuation with my friend HatedMoats. I will give a brief summary about our conclusion in this chapter, and will provide a link to the original post. This is a very extensive DCF exercise and I believe it truly reflects CSU’s current undervaluation. Lets start with the metrics first.

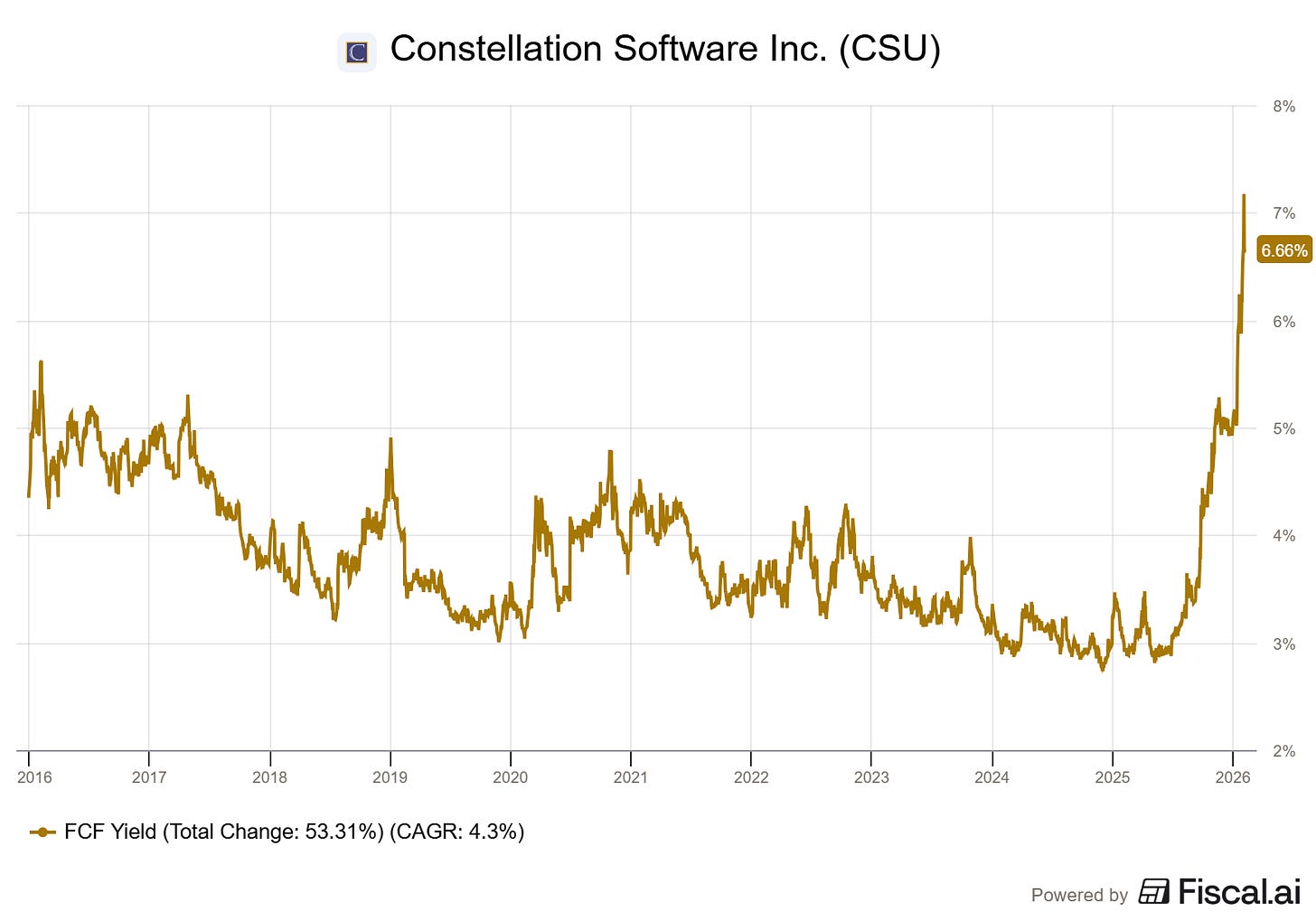

11.1 Free Cash Flow Attributable to Shareholders (FCFA2S) Yield

So, in my opinion the best way to properly get a quick look on valuation for CSU is the FCFA2S Yield

Why this specific metric?

As we concluded in the last chapter FCFA2S gives an honest look into the cash flow, because it subtracts several things that standard FCF often does not account for.

We calculate it as follows: FCFA2S / Marketcap x 100%

The current FCFA2S is $1.74B

The current market cap in dollars is: $38.55B

That gives a The FCFA2S yield of about 4.5%. Unfortunately, fiscal AI does not show this specific metric. So the next best thing is the ‘‘regular free cash flow yield’’, which you can see in the picture above. This trend and uptick is the exact same for P/FCFA2S.

Both the regular yield and the FCFA2S sit at decade high levels, pointing towards current undervaluation.

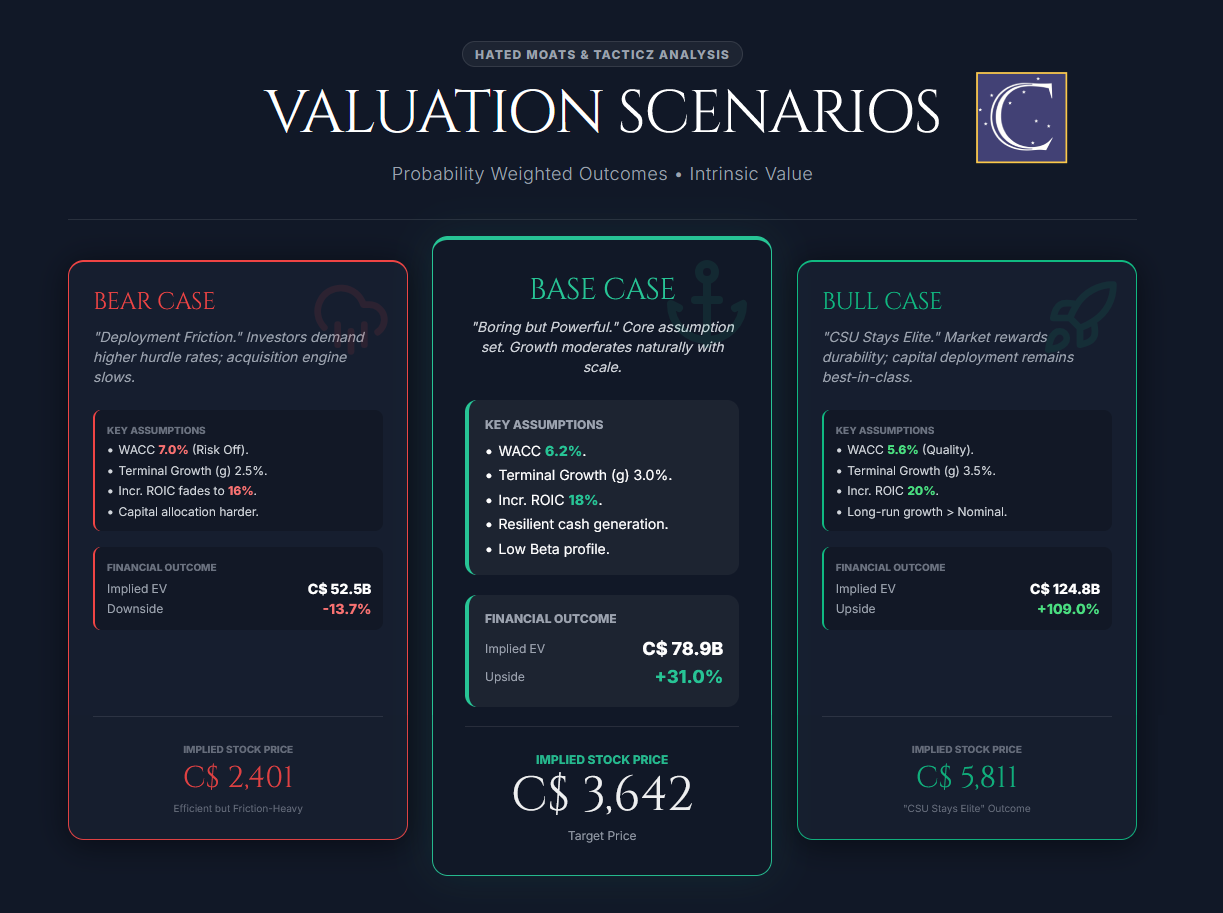

11.2 DCF-Model

Now, the DCF-model, which was a collab with HatedMoats. Here is the link to the full article, but I will summarize our findings in this part. Keep in mind this was done 2 weeks ago. So the valuation might have changed a bit in the meanwhile (the price dropped even further).

I am not gonna bore you with all the details and input that we used to get to our scenarios. You can read that in the original post.. Here is an overview of the valuation scenarios and the main assumptions that were used.

11.2.1. Bear Case

The bear case scenario leads to a fair value price of $2401 CAD per share. In this bear case scenario we account for weaker growth, a higher WACC, lower terminal growth and and an ROIC of 16%.

WACC: 7.0%

Terminal Growth Rate: 2.5%

Incr ROIC: 16%

This is just below the price CSU sits at today, which is around $2500 CAD

11.2.2 Base Case

The base case scenario leads to a fair value price of $3642 CAD per share. Which provides significant upside from today’s price. WACC is slightly higher than in the bear case, and higher growth plus ROIC rate lead to very reasonable upside from current level.

WACC: 6.0%

Terminal Growth Rate: 3%

Incr ROIC: 18%

11.2.3 Bull Case

The bull case scenario leads to a fair value price $5811 CAD per share. Our assumptions are lot more bullish here, but I would still argue they are quite reasonable.

WACC: 5.6%

Terminal Growth Rate: 3.5%

Incr ROIC: 20%

To summarize: That means the following upside from today’s price ($2500 CAD)

Bear case: -3.96%

Base case: 45,68%

Bull case: 132.44%

If we apply a 20%/60%/20% likelihood to the scenarios we get a weighted average intrinsic value upside of 53.10%

12. Final thoughts

In the end, the whole CSU thesis comes down to whether you believe AI will truly disrupt CSU’s whole business and it’s subsidiaries.

While we should not close our eyes for AI, and the impact it can have, I think the fears are a bit overblown. CSU is part of the bigger SaaS meltdown, and I think they are unrightfully put on the whole ‘‘AI will kill this company-list’’.

What you see is what you get with CSU. A well-run company, without any fuzz. A company built on core foundations, principles and norms and values. Still growing strong, and able to give meaningful shareholder returns.

I believe from this point, the risk/reward starts to heavily skew to the upside. If and when the whole SaaS meltdown starts losing some gas, and investors will again start to realize, CSU is not like most of these other SaaS companies, thing might start to look different very fast.

Sentiment in the sector might get worse, and a quick turnaround is not necessarily in the cards. But eventually, the stock price will be reflected by CSU ability to deploy cash, at high IRR. It’s simple as that.

If they are able to continue doing just that, it will reflect in the stock price.

The more I dove into Constellation Software, the more I realized what a great, well-ran company this is. It perfectly fits with how I approach investing myself.

It’s non-hyped, self-critical, sometimes a tad boring, focused on execution and always honest. This is not a company that is focused on short-term returns. They don’t need hype.

Whether you like CSU or not. I think it’s a perfect show-case of how you can built a company around core values, vision and a strong focus on execution.

This is not a story that will be replicated anytime soon.

But a story to learn from nonetheless.

My position

As a final disclaimer: I have been building a position in CSU in these past weeks. My plan is to continue building it into a core and meaningful position, as I believe this is a company that really resonates with me and fits me investing principles. I share my all my buys/sells and portfolio in realtime with my paid subscribers. So if this is something you are interested in, be sure to try it out!

By becoming a paid subscriber you also get access to:

All my portfolio updates (26% CAGR since 2023 - 31% in 2025)

Chat access and real-time updates on my buys and sells

Access to my discord and private community (opened yesterday)

Earnings updates

My archive of deep dives and posts (like ASML, Novo Nordisk and Kraken Robotics)

Exclusive content I make for my paid subs ( just like this post:

13. Closing words

If you have made it this far, thank you! I hope it was worth your time.

Keep in mind that I’m not an expert in this sector or a financial analyst. This deep dive is my own research and my attempt to understand CSU just a bit better than I did before. I’m just sharing my insights and thoughts here.

I would highly appreciate any feedback, negative or positive. I’m here to learn and I’m sure there is a lot more to uncover here.

Any like, share, repost/restack or comment truly helps me out.

Support me

If you’d like to go a step further and support the work behind the scenes, you can choose to become a paid subscriber. Your support helps me dedicate more time to researching, writing, and uncovering opportunities in value investing. My end-goal is to do this fulltime, but for now it’s just a faraway dream and a great side-project.

Below is an overview of my other deep dives.

Whether free or paid, I’m grateful you’re here. Your support makes this work possible and keeps me motivated to make more.

Disclaimer below.

Cheers,

TacticzHazel

Disclaimer

The content I share is for educational and informational purposes only. It should not be considered financial, investment, or trading advice. All opinions expressed are personal views and are not guarantees of future performance. Investing involves risk, including the potential loss of capital, and past results do not indicate future returns.

Before making any investment decisions, you should conduct your own research or seek guidance from a licensed financial advisor. I am not responsible for any financial outcomes resulting from actions taken based on the information provided.

By engaging with this content, you acknowledge and agree that you are solely responsible for your own investment choices.

I’m all for CSU, but your WACC seems way too low. The premium over U.S. Treasuries is minimal, and even if the beta is indeed low - say 0.7-0.8 - something in the 7%–9% range probably makes more sense.

That said, I also think using an LTM valuation is less appropriate. We’re already in Q1/26, and LTM still includes Q4/24. It would be more reasonable to think in terms of 2026 FCFA2S. If we back out the IRGA liability (which isn’t really a liability), we’re probably looking at roughly $2.2–$2.3 billion USD in 2026, which implies a multiple of around 16x.

Great breakdown of the VMS moat. Your point in section 7.3 about "institutional memory" is key—CSU’s 30-year database of failures is the ultimate defense against AI disruption, as "vibe-coding" can't replicate decades of niche legacy data.

However, struggling with the Mark Miller transition. If his Volaris model—reinvesting FCF locally rather than sending it to the parent—is now the lead strategy, doesn't his promotion signal the "death" of the classic CSU model? If every unit stops upstreaming cash to grow autonomously, does CSU eventually stop being a unified compounding machine and just become a loose collection of ETFs?